Veldhoven is a non-descript, largely modern, commuter town to the west of Eindhoven – itself a non-descript city dominated by Philips, the multinational Dutch electronics company. It is an unlikely setting for a company that lies at the heart of the developing semiconductor (chip) war between the United States and China.

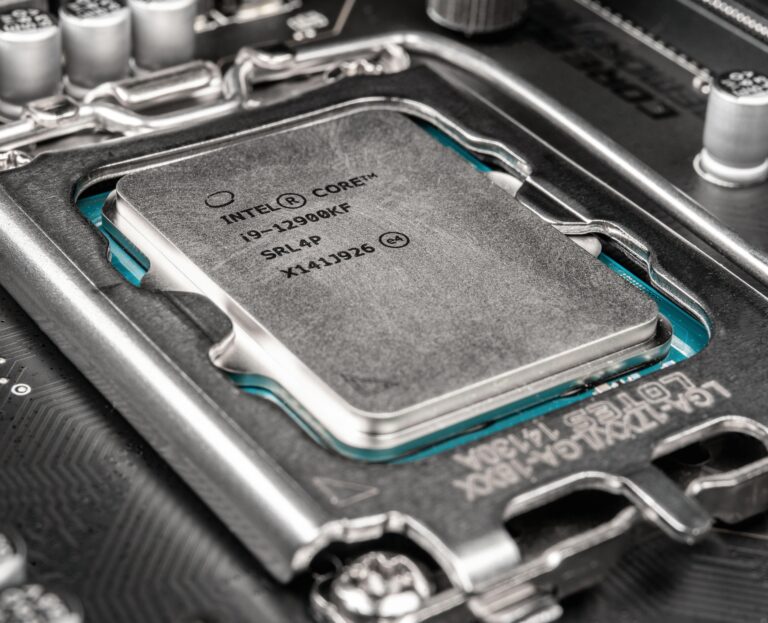

ASML Holdings N.V (originally Advance Semiconductor Materials Lithography), headquartered in Veldhoven, is the world’s leading manufacturer of semiconductor lithography equipment; its current machines, the size of a double decker London bus, cost US$150m, not including extensive service contracts. Lithography machines are the most complex component in the manufacture of chips.

ASML’s most advanced machines print the ultra-fine patterns on chips that can be as narrow as 3 nm (nanometres) on a 22 cm chip. To put this in perspective the typical width of a human hair is 70,000 nm. ASML machines can put up to 250 billion transistors onto a single chip. Founded in 1984 in a shed within Philips’ Eindhoven complex, ASML’s market capitalisation is now €200bn versus just €12bn for its erstwhile parent, making it the fourth largest company in Europe behind Shell.

In 1960 the first semiconductor announced to the world by Robert Noyce (a co-founder of Intel) comprised just 4 transistors. Over the last 60 years every sector of a modern economy owes a debt to advances in lithography to produce ever more powerful chips, notably computers, defence, mobile telephones, DNA genome sequencing, satellites, robotics, automobiles, and artificial intelligence.

That is the past but what about the future? Same story. Access to the most advanced semiconductors and their myriad of varieties are central to continued industrial competitiveness in the world’s most advanced economies.

That is why ASML is so important. It possesses that rare commodity – a market monopoly. In the 1980s and 90s the lithography market had been dominated by Japanese camera companies Nikon and Canon. That all changed in 2004 when ASML developed immersion lithography and latterly Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography. The company’s market share has doubled to 65 per cent over the last twenty years but in the sub-13nm market its share is 92 per cent.

Two months ago, the US government took the aggressive action to persuade the ASML and the Dutch government to ban the export of its Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography equipment to China. The ban is an attempt by the Biden administration to bar its geopolitical rival from access to the most advanced chips.

In recent weeks the US has doubled down on this China technology ‘denial strategy’. In response to new regulations ASML has sent an urgent memo to its employees ordering all US Citizens and Green Card holders, inside or outside of the US, to ‘refrain – either directly or indirectly – from servicing, shipping, or providing support for any customers in China until further notice.’ It is an interdiction that applies to all US manufacturers of semiconductor ancillary technologies.

The US has also banned Nvidia and Advanced MicroSystems – America’s global leaders in graphic processor chips – from selling its latest high-end products to Chinese customers. This is huge setback for Beijing’s ambitions in artificial intelligence and for Chinese corporations such Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu.

‘Technology denial’ is just one strand of the trade war that the US has initiated with China. The US attack on China’s bid to dominate future technology is twofold. The second part of the strategy is to rebuild America’s share of the global chip fabrication business, which has fallen from a peak of 37 per cent in 1990 to just 12 percent today.

In August the White House announced the ‘Chips and Science Act of 2022 designed to make ‘historic investments that will poise US workers, communities, and businesses to win the race for the 21st Century.’ $52bn of federal funds have been committed to the financing of technological research and fabrication of chips in the US. The EU has made similar noises but without the financial commitment.

The vulnerability of the West to semiconductor disruption has been made more urgent by the threat of an invasion of Taiwan, the world’s leading producer of semiconductors. The result is that there is an ongoing rush in Japan, Europe, and America to build semiconductor fabs. As well as completing the building of a fab in Oregon, America’s Intel Corporation is planning new fabs in Arizona and Ohio. Some $80 billion is also earmarked for Europe, with sites in Ireland, Germany and Italy being considered. The world’s largest fab company TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) and Korean semiconductor leader Samsung are similarly planning to build new fabs in Texas.

New fabs are technically challenging to build, and eye-wateringly costly. A recent study by Boston Consulting found the cost of a large chip plant is now more than an aircraft carrier or a nuclear power station. In Taiwan, Fab 18, which was built to produce advanced chips, cost US$17.5 billion.

Nevertheless, Intel has upped the ante by planning in 1925 to develop the first sub-nanometre ‘angstrom era’ semiconductor – a product that could put 400bn transistors on a single chip. At this level, the lithography process will need to be reduced to single atoms. A $300m order has already been placed for ASML’s next generation machine.

The US tech war with China has not gone unnoticed. At present China’s semiconductor champions are stuck at the 13nm level, leaving them several generations behind Taiwan. This gap is now likely to grow. It is no coincidence that in his ‘work report’ to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 20th National Congress last week, ‘Emperor’ Xi made clear that technology security is at the top of the agenda. Xi has urged China to increase its technological self-reliance and to ‘accelerate the pace of legislation in the fields of digital economy, internet finance, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing etc’.

The consequences of a chip war could be devastatingly – particularly if a Chinese invasion of Taiwan produces a complete disruption of East-West trade. We should remind ourselves of the present cost of the West’s proxy war with Russia – an economy ten times smaller than China.

Already the world is facing rampant inflation and slower growth with the prospect of recession in the major European economies. The consequences of the Ukraine War would be de minimis compared to a proxy or real conflict with China if Taiwan was invaded. According to the Nikkei Shimbun, a trade embargo of China after an attack on Taiwan would reduce global GDP by $2.61 trillion (2.7 percent). Other forecasters are much more pessimistic. Rand Corporation reckons that, in the event of an embargo of China US GDP alone could fall by up to 10 per cent ($2.3 trillion). But even that may be optimistic.

If globalisation has brought enormous economic benefits to the world since Deng Xiaoping’s deregulation of the Chinese economy in the 1980s, de-globalisation, the retrenchment to national interest and autarky, is likely to bring the world slower growth, or worse - war. Both America and China will be losers in their chip war. As the ever-wise Henry Kissinger has implored, China and the US need to ‘avoid a direct confrontation’ over Taiwan – an issue ‘that cannot be at the core’ of their relationship. Indeed, global peace and prosperity should be their focus; but where are the wise leaders needed to step forward?

Sie müssen sich anmelden, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Noch kein Kommentar-Konto? Hier kostenlos registrieren.

Taiwan is part of China, so China is the biggest producer of chips, isn't it?

So it is indeed.

What has changed is Chinas stance toward Taiwan. From peaceful reunification in the future to "we do not rule out a military liberation". The US has only reacted in a logical manner. Why give China teh means to build up a stronger military if it is a threat?