My hearing was virginally sensitive, my ear drum only gently rustled by the Swiss radio “hit parade,” when this brutal guitar chord blared through the open window of my slightly older neighbor, accompanied by an infernal drum roll. My pulse raced to a hundred and fifty as an abysmal voice roared, “Rrrrrrright ... now,” followed by a diabolical laugh. “Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-haaaa!”

Who on earth is playing that satanic sound? “Sex Pistols!” my neighbour shouted with a put-on serious face as if he was about to preach a new gospel.

“I am an anti-Christ / I am an anarchist,” the creature screamed in a lawnmower voice from his stereo. “Don't know what I want / But I know how to get it / I wanna destroy the passerby / Cause I .... wanna be ....Anarchy.”

Growing up in sleepy Swiss suburbia, I didn't understand a word at the time. I didn't need to. I understood intuitively. The way “Anarchy In The UK” breaks into the world of an adolescent is absolutely disturbing. To this day, I haven't recovered.

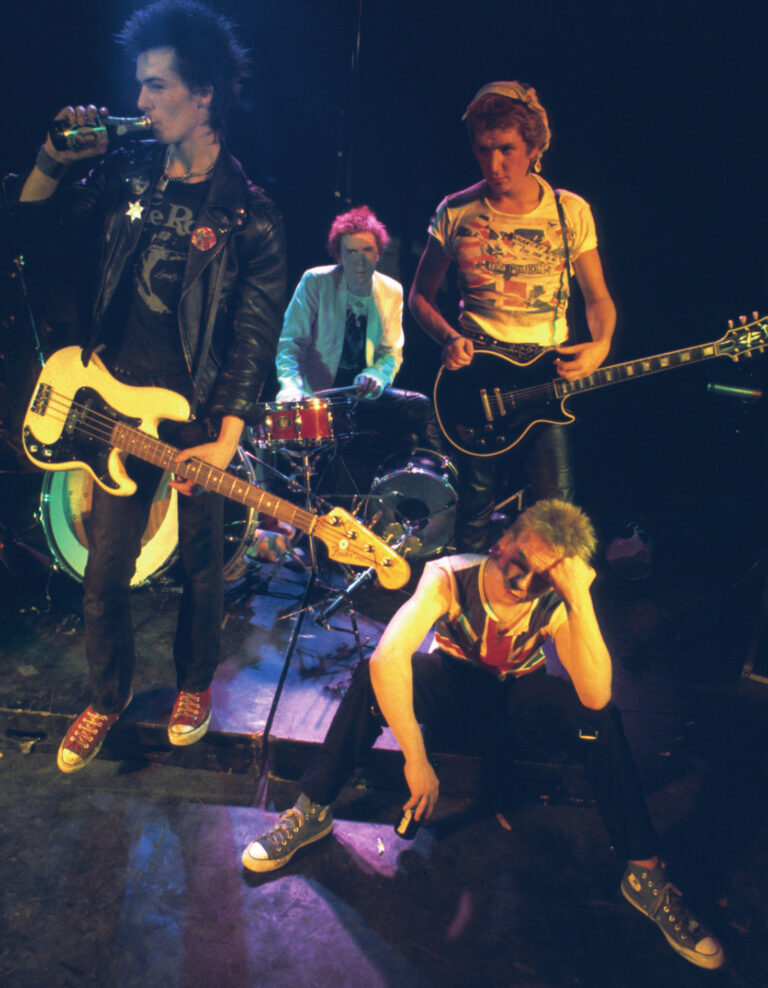

The Sex Pistols were a bolt from a grey sky that synchronously struck every Western city, from London to Sydney, with a brutal clap of thunder. The hippies dropped their joints on their well-worn Persian rugs.

The Sex Pistols' manager, Malcolm McLaren, described the debut single, “Anarchy in the UK,” as a “call to the kids who think rock'n'roll has been taken away from them. It's a statement of self-determination, of ultimate independence.”

McLaren had a way of impregnating anything with meaningful-sounding verbiage. He and Johnny Rotten, the legendary Sex Pistols singer with the lunatic look and gauche movements, have spent years managing the band's legacy.

They're done with that now. McLaren has been dead for twelve years. Johnny Rotten has been put in his place by a court ruling.

Academy Award winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Billionaire) has filmed the six-part miniseries, “Pistol.” It is based on the book by Sex Pistol guitarist Steve Jones, “Lonely Boy,” revealing new insights on how the establishment was shaken to its foundation.

And, now, it is Sex Pistol drummer Paul Cook to tell his version of the story. “Malcolm McLaren twisted our story as he went along,” says Cook as he sits down face to face with Die Weltwoche. “He was a manipulator … but he had no clue what was happening.”

‚Primal scream‘: Paul Cook

Weltwoche: The Sex Pistols electrified teenagers from Bern, Switzerland, to Sydney, Australia. Johnny Rotten's sneering voice to the frantic rhythm of your drums and Steve Jones milling guitar was like a wake-up call, focusing all the rage that had inexplicably built up in a teenager like a laser beam. Were you aware, at the time, that you were triggering a global awakening?

Paul Cook: Not at all, really. When we started, we wanted to cause something, cause a stir. The UK was a pretty grim place, at the time, in the late '70s. We were pissed off, and we tapped into a feeling of the kids at the time. But we didn't realize beyond our wildest dreams how it would tap into the feeling of unrest and discomfort for a whole generation and new generations which came after that.

Weltwoche: You and Steve Jones were the core of what later became the Sex Pistols. You have known each other since you were kids. What was this special bond that holds to this day and that has brought a revolution in rock?

Cook: We grew up together. We've known each other around our local area since we were 10 years old. We went to the same school. Our mums were friends. We just bonded over a love of music and fashion, really. Street culture has always been a very big thing in the UK, going way back to the Mods, the Rockers. That was our bond, and we were like buddies, brothers. Later on, we just thought, “Let's have a go. We love our music. Why don't we start a band?” It was just a light bulb moment, really.

Weltwoche: The music of the Sex Pistols sounded so different from the bands that were popular at the time — Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Queen, or all the art rock bands. How was that distinct sound created?

Cook: That was just a natural instinct. We didn't sit down and have a blueprint how this was going to sound. It was very basic because we were learning, still, at the time, as the Sex Pistols took off. It was just a natural anger and energy, I think, that came out inside of us from somewhere. It's like a primal scream, I guess.

Weltwoche: The movement that was set off by you and the Sex Pistols was soon called “punk.” Where did that term actually come from, and how comfortable are you with the label?

Cook: We didn't think of that name. Punk did have its roots in America, I guess, but we wasn't really influenced by American bands at all. We invented our own music and our own scene. I think it was the press that invented the term, really, and I guess it just stuck. They just start calling us these “snotty nose punks with attitude.” People like to label things and put things in bags, and it's still going to this day. We're playing the punk festival in Blackpool tomorrow. It's great. I'm totally comfortable with it.

Weltwoche: In his book “Lonlely Boy, Tales from a Sex Pistol,” Steve Jones writes of you: “There's always at least one weird introvert in a band. For me, in the Pistols, it was Cookie.” How did you observe the Sex Pistols from behind the drums?

Cook: I guess I had the most stable upbringing of everyone in the band. I was fittingly put, I started to learn the drums. I was the one at the back holding it all together while all this mayhem was going on in front of me, and I could see it. I guess there has to be one semi-sensible person in the band. I was just trying to hold it together while all this madness was going on out front because Steve was crazy. John and Sid, as well. Like Steve said, there has to be one sensible person in a band.

Weltwoche: You were the only one with an apprenticeship. Did you feel uneasy at times when it just got extremely wild?

Cook: Oh, yes. I think we all did. When the punk scene exploded in the UK, in '76, '77, it was national news. All over the papers, headline news, on the news, on the TV, everything. As you know, we'd done the famous Bill Grundy interview. Everything just exploded after that. We were like public enemies number one, at the time, and we were targets for people. There was all this negative press about punk. People wanted to attack us and beat us up. All these reactionary people who thought we were terrible for the youth of today and that we're corrupting everyone. It was pretty scary at times. It was for all of us, not just me, I think.

Weltwoche: The Sex Pistols were born in a shop called “Sex” on Kings Road that was run by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. What kind of people gravitated around that shop? How important was it, really, for the formation of Sex Pistols?

Cook: Oh, the shop was pivotal for the formation of the Sex Pistols, originally. I guess it was the only shop, at the time, that was doing something different and selling different clothes. People like Steve and me gravitated towards it because we wanted something different and we could hang out there. Malcolm was very accommodating. Let us hang out in the shop. They had a jukebox in there.

Then we were looking for a bass player. Glen (Matlock) worked in the shop. So, there was the bass player. Then John (Lydon) used to come in to do shopping and, hey, “presto!” There was the singer. Malcolm, the manager, was in the shop. It's amazing how it all came together. It was meant to be. All the planets were lined up, and then we just evolved.

Weltwoche: In 2008, I met Malcolm McLaren for an interview, which turned out to be one of his last. He told me, “Punk rock was the background music and the musicians were just mannequins, puppets that I arranged, positioned, and dressed with my creations.” Were you aware that you were simply McLaren's mannequins?

Cook: No. He made it up as he went along, Malcolm. He didn't know what was going on at the time either. He liked to take a lot more credit than was due, really. We could have been a band without him. It wouldn't have been the same, and it wouldn't have happened probably without him. But then he twisted the story as he went along. That's what really pisses me and everyone in the band off, really. That he pushed this image that we were all contrived and he made the band up, which is not true at all. Malcolm, I got not a bad word to say about him, really, apart from that. He did like to “elaborate,” shall we say. He liked to be liberal with the truth, as it were.

Weltwoche: [chuckles] Johnny Rotten once called McLaren the “meanest man on earth.” Some people call him a Svengali. What was he like?

Cook: He was a manipulator. He's a very unique character, Malcolm. He, like us, really wanted to shake things up. He was a bit of an agitator. He came from that '60s culture of the Paris Revolution, and the Situationists, and people like that. I think we were the perfect vehicle for him to get involved with, as well. It was five people, really. It wasn't him and us. We was like a team with him, as well. He was like a fifth member, if you like, and the whole team around it with Jamie Reid, the artwork, and Vivian (Westwood), and other people surrounding our scene. A very small scene, but they're all very unique individuals, at the time.

Weltwoche: The names “Johnny Rotten” and “Sid Vicious,” did McLaren create them?

Cook: Malcolm probably likes to take credit for the names. He did come up with the name “Sex Pistols,” for sure. But he didn't name “Johnny “Rotten” or “Sid Vicious.” Me and Steve formed that. We just used to joke about John. We were saying, “Oh, you're really rotten!” Because he was.

Weltwoche: He had rotten teeth, I hear.

Cook: Yes. And Sid, “You're so vicious.” The names just stuck.

Weltwoche: You were getting popular around London after the launch of the first single, “Anarchy in the UK.” But then, one winter evening in December in '76, you were catapulted into national headlines. You appeared on the Bill Grundy “Today” show which was aired daily at 6pm. The whole nation was watching, and the show became a scandal that shook the kingdom. What exactly happened during these few minutes?

Cook: It was very weird. I think we just signed to the record label EMI. I believe Queen were meant to be on the show because they were on the EMI at the time, as well.

Weltwoche: Queen, the number one rock band in the establishment at the time, cancelled their appearance at short notice “because their singer Freddie Mercury was having his teeth straightening,” as Malcolm McLaren told me.

Cook: They canceled, and EMI said, “Oh, we've got this new punk band. Why don't we put them on?” There was news, at the time, of the punk scene. It's been happening underground for about six months. Before the show, we'd all had a few drinks.

Weltwoche: There is rumor that Bill Grundy was drunk, as well.

Cook: Yes, I think he liked to drink, as well. He was well known for it, I think. He was being very antagonistic towards us. He was being very dismissive of us. I guess he asked for what was to come upon him, really. Steve was getting pretty drunk, and he was the main instigator.

Weltwoche: Bill Grundy started cracking on a girl who was on the show with you, Siouxsie, who later formed the band, “Siouxsie and the Banshees.”

Cook: He did.

Weltwoche: She was standing in the background, and Grundy said: “We’ll meet afterwards, shall we?” Upon which, Steve came in with the big guns, calling Grundy a “Dirty sod. Dirty old man. Dirty bastard. Dirty fucker!” And, “What a fucking rotter!”

Cook: That was a trigger. It was just banter, at first, but it very quickly turned crazy. It was all over in a flash, but Steve's timing was fantastic.

Weltwoche: What were your thoughts when all this was happening? You must have felt the world collapsing there.

Cook: I was sitting there going, “Oh, what's going on?” We hightailed it out of the studio. Malcolm was freaking out. We honestly didn't know it was going out live on TV, honestly. That night, we just went out to a club drinking totally oblivious to all the mayhem we'd caused. All hell broke loose. We just woke up the next day, and it was like, "Wow!" The press were knocking on our doors, waking us up at our studio, chasing us down the streets, wanting pictures and wanted us to say something. That was the start of it, really. Life was never the same after that.

Weltwoche: EMI dropped you. Your concert tour was cancelled. Grundy lost his job. The odds were against you, but you still managed to keep going and actually came out bigger than ever before.

Cook: Lucky enough, at the time, we were in the studio a lot. We hid in the studio making “Never Mind the Bollocks.” We actually had to leave the country at a certain time. We got out. I believe we went to Germany, of all places, and got hassled by the police. We went to Berlin for a week. We just had to keep our heads down. The tour was canceled. It was pretty tricky times, really. It was difficult to be in a band.

Weltwoche: Then you shocked the UK again with your second single, “God Save the Queen.” It came out as the nation was celebrating the silver jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. You managed to do that with the “hippie label” Virgin and its boss Richard Branson. How did you pull that off?

Cook: Again, it wasn't contrived. We wrote that song about six months before the jubilee. We didn't sit down and say, “Oh, the jubilee is coming. Let's write an anti-queen song.” It was just a natural thing that evolved again. John wrote these lyrics. We were messing about in the rehearsal room coming up with songs.

The planets were lined up all the way along with the Pistols. After EMI, we got sacked from A&M after an incident in a night club. Then we signed to Virgin. Richard Branson, God bless him, was the only one who was up for the game. He changed this label from the hippie label. Everyone wanted to be on Virgin after that.

Weltwoche: “God Save the Queen” stormed the charts. And it actually was the number one selling record, but officially it only ranked second. How did this happen?

Cook: That was just a sign of the times again. The BBC banned the single. They wouldn't play it. It did get to number one. It was outselling everything. But they controlled it so that they made Rod Stewart number one. They just didn't want us at number one because of all the furor we were causing.

Weltwoche: Because you were an embarrassment for the Queen, probably. The lyrics were: “God save the Queen / She ain’t no human being / There’s no future / In England’s dreaming.” Steve Jones writes that you were chased down and even glassed. Do you remember some of these horrible incidents?

Cook: Yes, I do. At the time, there was another sub-subculture group called “The Teddy Boys,” and they made it their mission to be anti-punk. In the 60s, you had Mods fighting Rockers. It was very much like that with the Teddy Boys and the punks. I got attacked by some Teddy Boys. John got glassed in a pub, and I got my head split open by them. Them was scary times. We got out and played in Sweden. All our tour in the UK was canceled. We couldn't function as a band, really.

Weltwoche: Not only life in public, but life in the Sex Pistols turned sour. The characters in the band were so diverse, it was probably hard to keep you together from a certain moment on.

Cook: I think it was a lot to do with the pressure we were under, really, that caused a lot of tension in the band. John could be a very confrontational character anyway. That was his nature.

Outside pressure started to affect the band in a negative way, really. That's what made the band great, as well. The confrontation in the band, that's what made the music. Aggressive and energetic, if you like, I think the anger that was coming out in the studio. I think there was a lot of outside pressure that caused it, and it was so difficult to hold it together. I'm surprised we managed to hold it together as long as we did, really, considering what was going on.

Weltwoche: Then you traveled across the Atlantic to the United States and made a tour, and the band rapidly dissolved. As Steve writes, you and he “couldn’t stand being around Johnny and Sid anymore. You couldn’t turn round for a minute without Sid starting a fight … Then on top of that you had Rotten, who was on his own trip and basically thought he was God, by that stage.” How did you experience the end of the Pistols?

Cook: That was a different level. That American tour finished the band off, first time round. It was scary over here in the UK, as I've mentioned. But doing that tour down the southern states was really scary. The police were following us around. I always thought something really serious was going to happen to one of the band members. We had security with us, but we were trying to escape from them, and all sorts of mayhem was going on. We had cops on the stage. There were undercover cops following us around. Warner Brothers who signed us were terrified that we were going to get in trouble and cause a stir in the record label and all these sorts of things. We couldn't be around each other, really, because John was freaking out, Sid was freaking out, and we were freaking out, as well. It's scary just thinking about it, really.

Weltwoche: Over the years, you have reformed the band and briefly played together again. But the Sex Pistols only produced one record. Nevertheless, “Never Mind the Bollocks” did have an enormous impact on music history. What is the biggest unknown story behind the Sex Pistols?

Cook: I think what people don't realize is that we worked really hard at it to be a good band. We all came from a great musical heritage in the UK, which we grew up with, but all diverse tastes and all different factors got involved in the pot, if you like. I don't think people realized at the time, as well, what a good band we were.

There was a big rumor going around that we didn't even play on the album, it was somebody else. They thought, “Oh, they can't play this. They're terrible.” That we were manufactured up to that point, as well. We were a great band. It took a long time for some people to realize that, but it had an instant effect on everyone, now, the album. We did put the work in.

Weltwoche: Recently, Oscar-winning director Danny Boyle filmed the six part mini-series, “Pistol.” Johnny Rotten wanted to prevent the Pistols' music from being used in the biopic series. He called the series the “most disrespectful shit I’ve ever had to endure.”

Cook: We actually had to go to court to get the rights about a year ago because John has been very controlling over the years with the Pistols. He thinks that he has to decide whatever goes on with the legacy, et cetera, et cetera. We got really fed up with this. It was a series about Steve, not John. Danny Boyle wanted to make it. People put money into it. And John just said, “No. I want control of this.” We just thought enough is enough. We didn't want to, but unfortunately we had to end up in court, which was a horrible experience. Maybe John was a bit jealous that it wasn't about him. I don't know. I haven't spoken to him in many years, now, and probably won't now after the court case.

Weltwoche: How did you feel watching an actor playing you in the film?

Cook: I was watching it like that [holds his hand at his face and looks between his fingers]. Watching it through my fingers, really. Then I saw bits of it again. It gets better the more I watch it. It's strange. I am far removed from that era, now. It's nearly forty years ago. So, I'm able to be objective about it. The reaction to it has been generally really positive and fantastic.

Weltwoche: What is your take on the biopic?

Cook: I think Danny Boyle's done a great job. After all these years, our story still resonates. That's why people wanted to make a series about us. People are dying to see it. It's not going to please everyone. It's Danny Boyle's version of Steve Jones' book. There's a bit of artistic license going on, obviously. But, generally, all the stories in the series are based on reality.

Weltwoche: You kept on playing music, and you still do concerts. In fact, you're going to a festival today. And your own daughter, Holly, is a musician in her own right. What keeps you driving?

Cook: I reformed my old band, The Professionals, the band I had with Steve. But it's a totally different lineup, now. I've been doing that for a few years, now. We've had two albums out. It's just the love of playing live, really, that keeps me going. With all the aggravation involved in it, and there is aggravation in every band sometimes, it's how it works. It's just I don't know what else I would do. If I didn't do it, anyway, I'd be bored, really. I'm not full on with it. It's like a part-time thing, really. It's just a love of music, really. And it keeps me fit, as well.

Weltwoche: Would you do it again, all over again with the Sex Pistols?

Cook: Oh, yes. I probably would.

Weltwoche: No regrets? [laughs]

Cook: The only regret is that we didn't make it last longer. That's a big regret, that we didn't have time to evolve as a band, really, because of what was going on. I would have loved to have done another album with the original Sex Pistols, back in the day.

Weltwoche: What do you think is the legacy of that Sex Pistols era? Techno is the big thing today. Very often one can hear the punk vibe in that, the aggressive energy that moves thousands of people.

Cook: That era influenced people across many spheres of music. You can hear it everywhere. The Prodigy, for instance. They are totally punk bad ass. It influenced writers, artists, anyone, whatever they were doing, because the message was so simple. It was like, “Whatever you do, just have a go and do it. Don't be afraid. Just go out there and do it.” It still resonates to this day, which is amazing.

Sie müssen sich anmelden, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Noch kein Kommentar-Konto? Hier kostenlos registrieren.

Strange – for once the drummer is the quiet, serious introvert of the group? Didn’t work well, did it?

Great Interview! Sex Pistols 4ever!