Few countries have been as much mythologised and misunderstood than India in the post-war period. The founders of the Indian nation are largely to blame. Both Mahatma Gandhi and India’s first prime minister, Nehru, for the sake of nation building, fostered the mythology that India had always been a country. That was never true.

For many millenniums India was a region comprising hundreds of warring autonomous states. Occasionally parts were unified as under the Moghul, Sikh and Maratha Empires, but India was never a country. Prior to Independence, India consisted of separately administered crown possessions and 565 independent states with whom Britain had various types of management contract. India, as a country was ruthlessly centralised and turned into a nation state for the first time by Nehru’s Congress Party, not by the British government which had generally ruled India with a light touch.

Neither was the post-war Indian economy held back by the legacy of the British Empire as has been fondly imagined by the left. Britain’s legacy was indeed pernicious but not because of Empire; India’s feeble economic progress in the post-war years was hindered not by imperialism but by socialism emanating from the London School of Economics. The Congress Party under Nehru and then his daughter Indira Gandhi turned India into a neo-communist autarkic state that became a symbiotic adjunct to the Soviet Union.

The collapse of the Soviet Union finally forced India to open up to international capitalism under the prime ministership of Narasimha Rao, the most underrated reforming politician of the modern era. Since 1991, though India has yet to become the exporting powerhouse that is China, its economic advance has been quietly successful; unlike China the key drivers have been its libertarian societal values and intellectual creativity.

India is already the world’s third largest economy in the world and, based on current trends of population (1.4bn people) and growth (5-7% per annum), its GDP will overtake the US by 2050 and China by the end of the century. But while the Chinese recognize India as their long-term economic and geopolitical rival, the West dozily continues to underestimate the sleeping giant. The Ambani family story is a parable of the awakening of modern India.

In Bombay (Mumbai) the weather varies from very hot and humid to unbearably hot and humid. In the four years I lived there, I can only remember wearing a pullover on one occasion. Is this the reason why Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, has installed a snow room in Antilia, his ‘bling-tastic’ new Bombay home? Press a button and the ice carved room fills with freshly made snow.

This no ordinary home. It is a palace that, for over-the-top ostentation, would make any Bond villain blanche. Antilia is a 60-floor tall, 40,000 squ.m building in Bombay’s most expensive neighbourhood, Altamount Road. Ambani built it for himself and his five family members in 2014. At a cost estimated at US$2.0bn, Antilia is reckoned to be the most expensive private house in the world and has become a landmark tourist attraction.

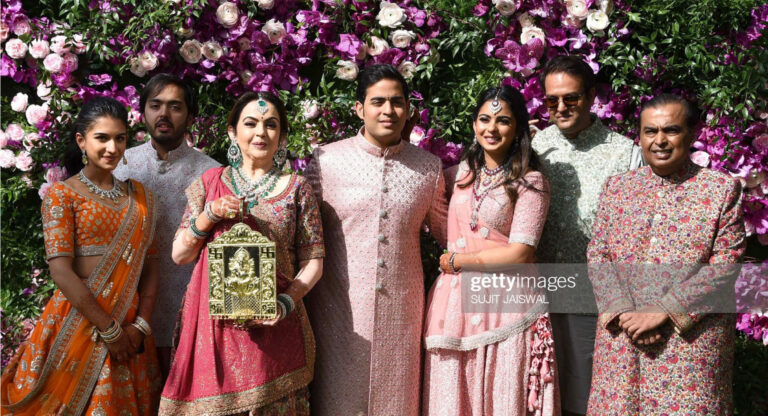

The family live on the top six floors reached by a bank of 9 elevators from the imposing lobby. Facilities include a 168-vehicle garage, 3 helipads (illegal), a ball room, a 50-seat movie theatre, a yoga studio, a dance studio, hanging gardens and accommodation for 600 staff - one hundred for each family member. There is also a Hindu temple. The family are devotees of Srinath, an incarnation of Lord Krishna, and make frequent pilgrimages to his temple by corporate jet to Udaipur from where they drive north to Nathdwara.

In recent years the family has started to pick up trophy assets overseas. Hamley’s, the famous Regent Street toy store has been acquired as well as Stoke Park, the magnificent Georgian Mansion which serves as a hotel and clubhouse for the golf course that featured in the Bond film ‘Goldfinger’. Further pocket change was expended on the purchase of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in New York. However, after a lengthy courtship the Ambani’s have pulled out of the US$5bn acquisition of Boots, the leading British pharmacy business.

Given the highly visible ostentation and newsworthiness of his Bombay home, his relative obscurity globally is somewhat of a mystery. At one point thought to be the richest man in the world, Muckesh Ambani is still, according to Forbes Magazine, the tenth richest man in the world and Asia’s richest person. With an estimated wealth of US$90.7bn he is more than four times richer than Jack Mar, the eponymous Chinese entrepreneur who founded Alibaba. To put his wealth in context, he is US$25bn richer than Mark Zuckerberg, more than four times richer than Rupert Murdoch and thirty times richer than Donald Trump.

Mukesh Ambani was born in Aden, Yemen, on 18 April 1957; it was then a British Colonial port located at the neck that links the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden. The following year his father Dhirubhai Ambani, a Gujarati trader of the Vaisya (artisan, merchant) caste, moved back to India to set up a textile trading business with his cousin. For the next decade he was modestly successful but dissolved his partnership and in 1966 set up the company that would become Reliance Industries. Notably he launched Vimal, a brand specialising in polyester suits and saris, that became the market leader in India.

The family lived in a modest 2-bedroom apartment in the unfashionable southern tip of Bombay, Bhuleshwar, and he started his business out of a 33sq.m office with just a table and a telephone. From here he built Vimal into a nationwide brand. He soon did well enough to buy a 14-floor apartment building for the family in Colaba, which is the area of Bombay in which the Gateway of India and Bombay’s famed Taj Hotel can be found.

There is little doubt that a substantial part of Dhirubhai’s success was due to his skill in developing political relationships. According to Hamish McDonald, author of Ambani & Sons [2010] Dhirubhai sent briefcases full of cash ‘to politicians all over Delhi.’ Given the nature of the ‘License Raj’, the political system which decided when and where polyester factories could be built, it could not have been otherwise.

Having studied chemical engineering at the Institute of Chemical Technology, Mukesh went to Stanford Business School to do an MBA. It was never completed. His father recalled him to help run a business empire that had by now diversified into petrochemicals. Incorporated as Reliance Petroleum, these businesses were merged into Reliance Industry in 2002. Today petrochemicals along with oil and gas represent the core of Reliance Industry’s business.

Dhirubhai died in 2002 although there had been a gradual shift in power to Mukesh and his other younger son Anil after the founder’s first stroke in 1986. Dhirubhai was a man who invited strong opinions; for some he was a role model, for others ‘a schemer, a first-class liar’ while for others he was a ‘visionary’ and ‘Napoleonic’.

The death of Reliance’s founder produced the major crisis of the Reliance story – not a business crisis but a family crisis. Dhirubhai had left no inheritance instructions. Although Mukesh was made Chairman and Managing Director and Anil was made Vice Chairman there were continuous disputes. Their irreconcilable differences became public in November 2004. It took their mother Kokilaben Ambani to lay down a solution. In June 2005 assets were split. Mukesh got petrochemicals, oil and gas exploration, refining and textiles while Anil took away telecoms, power, entertainment and financial services.

But the battle for supremacy continued between the brothers. Over the next four years court action followed between over telecoms and oil. Ultimately it was Mukesh who won through. Firstly, he diversified successfully by branching out into food, clothing and housewares. Since 2006 Reliance Retail become the dominant player in the retail sector.

Secondly, Anil, always the ‘wild child’ of the family, who had spurned a traditional arranged wedding to marry a Bollywood star, over-leveraged his companies and fell foul of creditors including Ericsson Telecom and three Chinese banks. By 2019 Anil’s Reliance ADA Group had lost 90% of its market value. Facing personal bankruptcy and prison, eventually Anil had to be bailed out by his brother to the tune of US$77m.

A final blow to Anil was the destruction of his mobile telephony company Reliance Communications by Mukesh’s launch of Reliance Jio in 2016. Jio’s disruptive model provided faster and cheaper mobile and data services. It did no harm that Mukesh managed to co-opt the prime minister as a user of his service. As one subscriber noted, ‘Prime Minister Modi was endorsing Reliance Jio’s ad initially and I see him as my idol so I shifted towards Reliance Jio.’ Within 12 months Mukesh had bagged double the market share of his brother and five years later Jio commands a leading 36% share of the market. Anil’s Reliance Telecommunications filed for bankruptcy in 2019.

There is every indication that Mukesh Ambani has been as able a political fixer as his father. Mukesh is known to be a major backer of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who, like the Ambanis, is a Gujarati. The result of Mukesh’s political acumen and ruthless business tactics has put Reliance Industries conglomerate into a position of economic dominance in India which is unrivalled by any company among the world’s major economies. As one lawyer is reported to have said ‘Ambani is bigger than the government. He can make or break prime ministers.’ For the time being at least it seems that what’s good for Reliance is good for India.

Sie müssen sich anmelden, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Noch kein Kommentar-Konto? Hier kostenlos registrieren.

Den Leser interessiert die Geschichte Indiens vor 1949 um das Land im Kontext zu verstehen. Ihre "grösste Demokratie" welches die Briten - und Sie sind Brite durch und durch - in Stellung bringen wollen gegen China.

So eine primitive Geschichtsklitterung interessiert uns nicht! Behalten Sie ihre Weisheiten und ihr dümmlicher Geschichstunterricht für sich! Es gibt genügend intelligente Professoren der Geschichte, die ewtas über China und Indien schreiben könnten...

Sehe weniger "primitive Geschichtsklitterung" als vielleicht eher unreflektierte Überhöhung eines spezifischen Geschäftsmannes. Aber Sie haben ja recht, es gibt genügend dümmliche Verfasser von Kommentare in der WW – was brauchen wir noch den Senf von Professoren?