Is Asia on the brink of overtaking the West’s cultural dominance? It is now a commonplace to describe Asia as the manufacturing centre of the world. That mantel has long since passed from West to East. Soft power may now be headed in the same direction. Those Asian countries that have emerged as titans of soft power, Japan and Korea, have been the ones whose economies transited first from largely manufacturing economies to consumption and lifestyle economies.

Japan has been the early leader. Arguably Japan, an advanced industrial economy by the start of the 20th Century, was already having a significant cultural impact on the West. Famously the French impressionists had been influenced by the woodcut (Ukyo-e) work of Hokusai, Hiroshige and others whose work depicted landscapes as well the ‘floating-world’ of Kyoto’s geisha culture. In the late 19th Century Japan also brought to Europe their expertise in cloisoné enamel work. Later Japanese art and design would have a great impact on the architectural and design work of Frank Lloyd Wright who described Japan as the ‘most romantic, artistic, nature-inspired country on earth.’

Japan’s visual sophistication transferred to cinema in the 1920s. When a group of Hollywood directors reviewed twenty Japanese movies made between 1937 and 1941 they unanimously agreed that they were much superior to American and European movies. The legendary photographer and movie maker Frank Capra, after viewing Sato Takeshi’s film Chocolate and Soldiers [1938], acknowledged, ‘We can’t beat this kind of thing.’ In the post war era Japanese film makers, notably Akira Kurosawa, have been among the world’s most influential

In the 1920s the tradition of pottery as a fine art was brought to Europe by Japanese potter, Shoji Hamada, the Mashiko ceramicist, and Japanese Living National Treasure who played a significant part in turning the remote Cornish fishing village of St. Ives into an unlikely global centre of the modern art movement in the immediate post war period. Over the last decade Japanese migrants to London Akiko Hirai and Yuta Segawa have become major figures in the rapidly growing fine art pottery scene.

If we look at the world of fiction, besides the US and Great Britain, who dominate the all-time best sellers list, Japan ranks third with 17 writers in the top 100. Even then that list does not include Japan’s Nobel Literature Prize winners; having failed to win in the prize’s first 67 years Yasunari Kawabata won in 1968 followed by Kenzaburo Oe in 1994 and Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017. Over the last 20 years Haruki Murakami has become one of the world’s best-selling novelists, whose work has been translated into over 50 languages.

Another area of ‘high culture’ in which Japan has excelled in the post-war era is architecture. Since the introduction of the Pritzker Prize in 1979, often described as the Nobel Prize of architecture, Japanese architects have had seven winners including four in the last twelve years. Future winners could well include Kenga Kuma (Tokyo 2020 Olympic Stadium) and Yoshio Taniguchi (MOMA: Museum of Modern Art NY).

As for the culinary arts power has long since transferred to Japan; after training in Japan and running a Michelin starred restaurant there, an Anglo-Japanese chef disclosed to me that he was shocked by the relatively low standards that he found in Michelin restaurants in Europe. Tokyo is the world’s most Michelin starred city while Kyoto and Osaka rank 3rd and 4th.

In other soft arts Japan excels is fine art photographer where Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama and Hiroshi Sugimoto have established world leading reputations. Japan also has became a post-war leader in global fashion with designers such as Kenzo, Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto.

At the popular end of Japanese culture, manga and anime (animated manga) have introduced a new art form to the West. In some European markets Japanese manga have replaced was largely considered a children’s ‘comic’ format. Manga have 70% of the comic market in Germany while France accounts for 40% of all manga sales in Europe. This is an adult cultural format; Shigeru Mizuki’s highly regarded ‘Showa: A History of Japan 1926 – 1939’ is an epic manga that does not shy away from Japanese atrocities in the Sino-Japanese War including the infamous Rape of Nanking.

Manga sales are growing in the US where a Seven Seas Entertainment executive has recently reported ‘2021 will be the biggest year yet – we’ve truly never seen numbers like this. Meanwhile the popularity of anime was greatly boosted in the US by their extensive use in Quentin Tarentino’s movie ‘Kill Bill: Volume I’ [1983].

If Japan has led the way in Asian soft power in the post war era, it has been closely followed by South Korea, the real ‘miracle’ post war economy. In recent weeks Korean culture’s global reach has be witnessed by the extraordinary success of The Squid Game which, in terms of global hours watched, has thus far exceeded the next most watched Netflix drama by 75%.

It is not an isolated success. Cinematically, South Korea announced itself on the global stage when Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy [2003] a film noir, won the Grand Prix at the Cannes film festival. The crime comedy Parasite [2019] went more than one better when it became the first foreign language film to win the Oscar for best picture along with that for best Director.

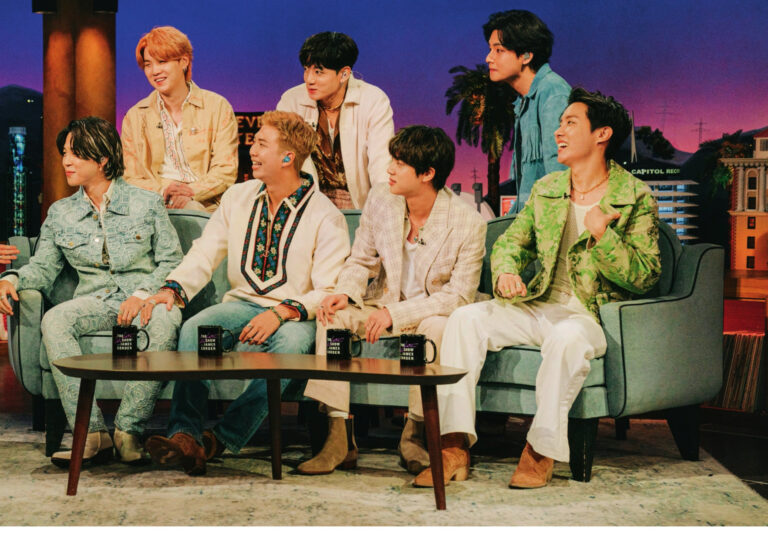

Even more successful has been the export of popular music. K-pop as a genre came into global focus with the release of Gangnam Style [2012] which became the first video to hit a billion views on Youtube. It has now been seen 4bn times. Since then, global interest in K-pop has boomed. In 2020, the fashionably gender-indeterminate 7-member boy band BTS (Bangtan Boys) became the first the first Korean number 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and the fastest act to achieve five US number 1s since Michael Jackson.

The US Kcon (K-pop conference) which had a few hundred attendees in 2012 is now a bicoastal event hosting 500,000 people. The Korean Ministry of Culture has been particularly active in promoting K-pop and recognizes the importance of an industry now estimated to be worth more than $5bn. Government support may have been critical to the promotion of this industry, but it is the digital streaming revolution that has made global K-pop possible. As DJ Steve Aoki has noted, ‘with streaming…the fans made it a phenomenon.’

Measuring cultural power is an imprecise business. But Japan and South Korea rank consistently highly in international surveys. In media group US News and World Report’s latest rankings of countries by cultural influence, Japan and South Korea come 5th and 7th respectively. Meanwhile the global culture and lifestyle magazine and media group Monocle ranks South Korea 2nd and Japan 4th.

Arguably, it is only in the area of sport that South Korea and Japan have lagged. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics was dramatically successful in promoting Japan’s both economic and spiritual recovery from World War II. Thereafter Japan’s impact on global sport was minimal. Both Japan and South Korea are clearly now trying to address this area. Japan has recently hosted both the Rugby World Cup and the Tokyo Olympics, which was a success in spite of the Covid pandemic. Seoul too held a successful summer Olympic games in 1988 and the winter Olympics in PyeongChang 2018 – an event described by the British Council as one of the best organised games of recent times.

Thus far world sports stars from these countries have been few. This may be changing. Tennis player Naomi Osaka broke the mould when she won the US Open in 2018. This was followed by the World No.1 ranking and three more grand slam titles. In golf, South Korean Y.E. Yang had a major golf tournament winner when Y.E. Yang defeated Tiger Woods to win the US PGA Championship in 2009. This year Hideki Matsuyama became the first Japanese player to win a major tournament, the Augusta Masters.

Where Japan and Korea have led in the realm of culture and soft power, it can be expected that the Asian behemoths, China and India, will follow. Given the size of their populations, economies and growth rates, if they achieve even half the success of Japan and Korea, their impact on the global cultural shift to Asia will be seismic. Current trends suggest that is not a question of if the West will yield cultural supremacy to Asia, it is a question of when.

Francis Pike is author of “Empires at War: A Short History of Modern Asia Since World War II”