Tank battles in Europe, nuclear missiles on alert, shortages of iodine tablets. Russian President Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine has resurrected the crises of the Cold War and, with them, fear of a nuclear apocalypse.

To help understand this precarious moment, Die Weltwoche turns to John Lewis Gaddis, Pulitzer Prize winner and Yale University professor of military history. Putin's war against Ukraine, Gaddis warns, is in the tradition of giant miscalculations of eminent leaders in history.

Like the strongmen of the former Soviet empire, Putin sits atop a political machine engineered to serve his ambitions, gloriously isolated from criticism and, crucially, common sense. ”Common sense is like oxygen,” Gaddis explains. “It gets thinner the higher you go.”

But Putin’s megalomania is only part of the story. Gaddis argues that the West deserves its share of the blame for the Ukraine catastrophe. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Empire, Europe and the United States failed to incorporate Russia into a peaceful, post-Cold War order. Whether out of hubris or lack of foresight, the error has been costly.

Weltwoche: For several years, there has been talk of a new Cold War. Is the term, "Cold War," really accurate? And are we now, after Putin's invasion of Ukraine, on the brink of a third World War?

John Lewis Gaddis: It seems to me that this is neither. Obviously, it's not World War III. And it does not fit the pattern of the Cold War as we understood the confrontation between the Soviet Union and the West in the period, 1949 to 1991. One way to look at this war (in Ukraine) is in terms of Russian invasions of neighbors. Russia did two major invasions in the Cold War period. One in Hungary in the aftermath of the Budapest uprisings in 1956. The other in Czechoslovakia in 1968. What is new in this situation is the incompetence of the Russians, because when they did invade in '56 and in '68, at least they did so fairly efficiently, and they were in charge of the country within a matter of a day or two. Ukraine is something totally different. They have gotten themselves bogged down in what is essentially a new and nearer Afghanistan, it seems to me, or worse.

Weltwoche: You remarked in a recent interview that although “the prospect of Ukrainian membership in NATO was extremely remote,” Putin used this “as a fabricated excuse for what he is really trying to do, which is to rebuild the old Soviet Empire, indeed maybe the old Russian empire.” And you added: “Putin has used this as a justification for his expansion just as Hitler used the presence of German speaking Sudeten withing Czechoslovakia as his justification for taking over that country in 1938.” Can you explain the point you are making here?

Gaddis: I was trying to make the point that the West, and particularly the Americans, bear some responsibility for this situation by having orchestrated a post-Cold War settlement that, in effect, excluded the Russians.

Previous settlements of great wars, hot or cold, can be divided into two categories, those that included former adversaries quickly, sought to reassure them, and incorporated them into the postwar security system on the one hand, and on the other those that excluded former adversaries. Those that included former adversaries were the post-1815 post-Napoleonic War settlement and of course the post-World War II settlement 1945. Both of those settlements proved to be durable and resilient. The 1919 Versailles settlement, however, excluded both Soviet Russia and Weimar Germany. It lasted only two decades, as we know.

I was making the argument that the expansion of NATO into Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, and with the prospect of further expansion while excluding the Russians, was indeed asking for trouble.

Weltwoche: You stand thus in the tradition of George F. Kennan, the intellectual father of America's containment policy during the Cold War, whom you have written a biography of that was awarded with the Pulitzer Prize. Kennan called the expansion of NATO into Central Europe “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.”

Gaddis: We were not very farsighted in setting up to post-Cold War settlement, but that in no way justifies what Putin is doing in Ukraine. It was perfectly possible into the late 1930s to criticize the Versailles settlement without, at the same time, defending Hitler's annexation of the Rhineland, Austria, and ultimately of Czechoslovakia. Those are two different things. I think that distinction has to be made.

Weltwoche: Let’s roll back the clock thirty years. NATO and Western countries were confronted with the urgent demand by, first, Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary, and then, further on, more states from Central Europe to accept their membership into NATO. Those nations had been suffering under the yoke of the Soviets for four decades. Should the West have turned down their security needs?

Gaddis: Not at all. I don't think that the West, that the Americans and their NATO allies should have disregarded those anxieties on the part of the Czechs, the Hungarians, and the Poles. My only question is whether NATO was the best instrument for dealing with them. Remember that NATO was a means, during the Cold War, toward the larger end of containing the Soviet Union. That mission was accomplished. By 1991, Soviet Union no longer existed. To perpetuate NATO, in a situation when its objectives had already been achieved, was hanging onto a process without specifying its purpose. That left NATO in search of a purpose after the Cold War ended.

Weltwoche: You argue that Russia has been excluded after the end of the Cold War. Historical facts prove the opposite. In the Charter of Paris for the creation of a new peaceful order in Europe in 1990, Russia was a substantial part. In the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan pledged to give up their Soviet-era nuclear weapons and hand them over to Russia — an enormous vote of confidence in the Russians. In 1996, Russia was admitted to the Council of Europe. In 1998, the G7 of the most important industrialized nations accepted Russia — although an economic dwarf state — into its circle. In 2011, the World Trade Organization opened its doors to Russia. In short: For two decades, the West actively showed willingness to include Russia as an integral part of a new world order. Meanwhile, it was Putin himself who steered away from Europe. He established a rigid autocracy in Russia and fought extremely bloody wars in Chechnya and Georgia. Later, he invaded Crimea. Isn’t it Putin’s own mistake that there was no deeper integration between the West and Russia?

Gaddis: The problem was the NATO expansion did not stop with the incorporation of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland. It kept going. That had Kennan's objection to the formation of NATO half-century earlier. He said, "Once you start this process, everybody will want to join it. There'll be no logical point at which you stop it. NATO will become larger but less defensible because of the expanded territory that's being included."

Of course, that's precisely what happened. NATO was expanded into the Balkans and, with the Baltic States, even into the former territory of the Soviet Union. Then there was talk, in 2008, about the incorporation of Georgia and Ukraine into NATO. This took place unilaterally without considering what the reaction of Russia itself might be. This was careless. It was done without a sense of strategy.

Weltwoche: What more should the West have done to better integrate Russia?

Gaddis: My own view was that NATO was an extremely useful organization during the Cold War and that some security structure, maybe or maybe not called NATO, could have reassured countries about their security in the post-Cold War period. I favored extending it to all of Eastern Europe with an offer to the Russians themselves to join the arrangement, just in the same way that France was invited to join the Concert of Europe after Napoleon’s defeat, and that after World War II, West Germany and Japan, were invited to join the Western security structures. That I think is what should have been done. And that would have been a good time to pursue it because, at that point, nobody had heard of Mr. Putin. Boris Yeltsin was running Russia and would be running Russia for that entire decade of the 1990s. We could have dealt with him, I think, in an amicable way. Our failure to do that, it seems to me, then paved the way for someone less amicable, shall we say.

This again is not to justify what Putin has done now, which is totally inexcusable. Which is why I think Putin will be out of power soon as a result of having done this.

Weltwoche: In the meantime, the fighting is getting uglier day by day, and it is obvious that Putin’s war not going as planned. In an interview with this paper last week U.S. General Petraeus said that Putin “miscalculated very, very badly” in Ukraine. It makes one wonder if Putin's underlings have been too afraid to tell him the truth about the capabilities of his armed forces all along.

Gaddis: I always have the greatest respect for whatever General Petraeus says, and I think he's absolutely right about this. I would add, though, a couple of points. One, which was not a surprise, is that the command structures within the Russian army are very centralized. It is not possible for units at lower ranks to do anything without consulting the highest authority and that's a cumbersome process if you have to run an army that way. The Americans run their militaries in opposite ways, so that even at lower ranks, people know what to do and do not always have to consult and get permission from the top.

The second and larger point is that authoritarianism in general has trouble delegating authority. That indeed is practically the definition of authoritarianism: it does not delegate. If the man at the top has to design everything, then chances are he will only be told what he wants to hear. There's no question in my mind that that is happening in Russia right now.

Weltwoche: Has Putin been misled by his top brass all along about his army's state of readiness?

Gaddis: The very image that we have of this little man sitting at the end of a very long table with his advisors pretending to give him advice is a visual representation of authoritarianism like no other we've had in the recent past. That is a fragile form of government because it detaches itself from reality. What makes it even more so it that in an authoritarian system there can be no orderly succession. Authoritarians can’t designate their successors because they immediately become rivals. And so the system is stuck with its current leader until that current leader grows old, senile, and feeble, and ultimately dies. Leadership gets entrusted to zombies.

Weltwoche: This is indeed reminiscent of the Soviet Union.

Gaddis: We saw something like that in the Soviet Union in the first half of the '80s, when there were real questions as to whether the leaders of the Soviet Union were in fact alive or not. That's where authoritarianism leads. This risks being Russia’s future now, it could conceivably be China’s as well under the rule of Xi Jinping. This is why authoritarianism is not, in the long run, a strong form of government.

Weltwoche: The Cold War was characterized by the doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD). Each side knew that pressing the nuclear button would mean its own demise. Nevertheless, the nuclear threat was always there. How much depended on bluffing during this period? Is Putin bluffing when he now threatens to use nuclear weapons?

Gaddis: There was a considerable element of bluff during the Cold War. In fact, the whole strategy was to keep the bluffs as bluffs and not actually implement them. That was the logic of mutual assured destruction. All that Putin has done so far is to talk about the possibility of using weapons not used before. This was, I think, more a rhetorical alert than an actual alert. I haven’t seen evidence yet that Russian nuclear forces were deployed differently.

Wetwoche: During the Cold War, the world came to the brink of nuclear war several times. Was there a comparable situation of a public threat with nuclear weapons as Putin has voiced?

Gaddis: The most recent moment in which the Americans did something like this was during the1973 Arab-Israeli War, when Nixon was distracted by the Watergate crisis and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, declared a nuclear alert. That was a real one, immediately evident to Russians. They immediately backed down from what they had threatened to do, which was to settle the Arab-Israeli dispute themselves. The alert lasted only for a day or so, at which point the Russians backed down.

Weltwoche: In your book, "On Grand Strategy," you analyzed high-risk operations by great rulers: Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Hitler at the gates of Moscow, Lyndon Johnson in Vietnam. All of these leaders were blinded by their earlier tactical successes and eventually ended up humiliated or dead. Is Putin's war against Ukraine in the tradition of such miscalculations?

Gaddis: Yes, I think it is. What I said in the book was that common sense is like oxygen: it gets thinner the higher you go. One of the things that causes you to go high is military success. This was the case with Xerxes of Persia, it certainly was the case with Napoleon. Mr. Putin too has achieved some easy successes, for example his chopping off pieces of Georgia, and his seizure of Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine. None evoked firm responses from the West.

So, he could conceivably have told himself, “Why not all of Ukraine?” This illustrates the high altitude problem, altitude because common sense would have told him that Ukraine is very different from Crimea, or from one or two provinces in Georgia. Ukraine is territorially, apart from Russia itself, the largest European state. To say that it was going to be a pushover, to say that you could do this in 24 or 48 hours, shows a complete absence of common sense. This goes back, then, to the seductive effect, upon authoritarian leaders, of cheap successes. What Putin has gotten instead is a continuing failure – an Afghanistan on his very own doorstep – the effects of which are not going to go away any time soon.

Weltwoche: Putin imposed three conditions on the West before the war: “First, to prevent further NATO expansion. Second, to have the Alliance refrain from deploying assault weapon systems on Russian borders. And, finally, rolling back the bloc's military capability and infrastructure in Europe to where they were in 1997 when the NATO-Russia Founding Act was signed.” In other words, the NATO extension should be completely rolled back.

Gaddis: And of course that’s completely unrealistic, all the more so in that Putin has not yet achieved the military victories that would make such demands even remotely plausible.

Weltwoche: What could a possible solution of this war look like, an agreement that is face-saving for all parties?

Gaddis: It's hard to know for sure, but there are some things that are perfectly obvious. The first priority would be a ceasefire to stop the violence, and the resulting humanitarian outrages. A second priority, I think, would be a withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine with the possible exception of Crimea which is 90% Russian anyway, and and whose 2014 annexation the West did nothing to prevent. The Donbas provinces could be negotiated: their separation from Ukraine shouldn’t be automatic. There’d have to be some provision for reparations: the burden of rebuilding Ukraine should not fall exclusively on the Ukrainians or their western allies. In return for which Ukraine could agree to stay out of NATO, as Finland, Sweden, Austria, and Switzerland have done, while not precluding membership in the European Union. Finally, there’d need to be assurances, in one form or another, of mutual respect on the part of Russia and Ukraine for each other's sovereignty. Ukrainian president Zelensky seems to be moving toward something like the above. Whether Putin will do so is not yet clear. His refusal to do so, though, will I think hasten the end of his rule, and thus bring nearer a post-Putin era in which more promising opportunities for all concerned may reside.

How likely all of this is no one can tell, at the moment. That’s no reason not to plan ahead, however, for that moment, if and when it comes.

Weltwoche: Back in 1947, Kennan predicted that the Soviet Union would not collapse from war but from internal contradictions. He was absolutely right. But it took much longer than he thought. What are the chances that this will happen to Putin's Russia? And how long might it take?

Gaddis: I think Putin's Russia doesn’t have much time, because it’s gotten itself into an untenable position. Partly from the almost universal condemnation it’s provoked in the rest of the world, partly because of the unity it’s inspired among the US and its European and Western Pacific allies, partly because of the unprecedented sanctions these have made possible on an already unhealthy Russian economy, but also because others in and around the Kremlin will be asking themselves how long they want this incompetent to be running the country.

Ultimately, the Russian people will have a say in this as well because of the current level of war casualties. Conservative estimates count 7,000 Russian troops dead in the first three weeks of this war. That's an extraordinary casualty rate. There's no way you can cover that up, when the bodies start coming home to be buried cemeteries across Russia. That will be a very powerful thing indeed.

Weltwoche: You have spoken of the mistakes that the West made toward Russia after the Cold War. What needs to be taken into account when building a new security order so that Europe does not end up in a bloody confrontation again?

Gaddis: We should be asking ourselves a few questions: Should we continue to expand NATO? If so, where and for what reason? Would it not be better to rethink the whole question of what NATO was historically intended to do? And to think innovatively about new post-Putin era, in which we could start over and build a structure of peace that would include Russia? Keeping in mind that we all – including Russia – will for the rest of our lives face the need to balance a rising China? Something like that I think is where we should ultimately try to go.

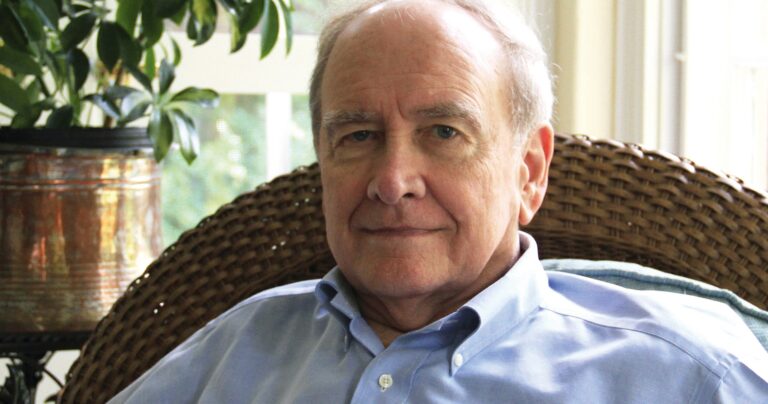

John Lewis Gaddis, 80, is a leading researcher on the Cold War. His book "The Cold War: A New History" is considered one of the best works on the era. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his biography "George F. Kennan: An American Life," published in 2011. Gaddis is the Robert A. Lovett Professor of Military and Naval History at Yale University.

Eine sehr nüchterne Analyse. Über weite Strecken richtig. Wie immer gibt es ein Aber. Wer weiss wie es ausgehen wird? Sicher niemand. Richtig ist es auf gar keinen Fall was da abgeht. Fakt, dass der Selenski eine NATO Marionette ist, kann man nicht einfach so ausblenden. Ebenfalls erwiesene und erfahrene Beweise, dass die USA-NATO Kompanie unliebsame und nicht kontrollierbare Regierungen mit allen Mitteln zu stürzen versucht. 30% Arbeitsplätze in USA brauchen einfach immer Krieg. Sehr schwierig

Der ehemalige deutsche Botschafter Rüdiger von Fritsch beschreibt, wie Deutschland nach dem Zusammenbruch der SU alles versucht hat, mit Russland eine faire und enge Partnerschaft aufzubauen. Das scheiterte. Dann kamen die diversen Überfälle von Nachbarn, Georgien, Tschetschenien, Ukraine. Neben zuvor 1953, 56, 68 usw. Wie sollen denn vertrauensbildende Maßnahmen in der Post-NATO-Zeit aussehen?

Sehr gute Analyse eines sehr guten Experten erfasst von einem sehr guten Journalisten. Danke! Ich teile alles zu 100%. Mit Jahrgang 1954, 2 Uniabschlüssen, 1300 Diensttagen in der Schweizerarmee und 40 Jahren selbständiger Berufstätigkeit plus Politik traue ich mir zu, richtig zu liegen. Die Hooligans der anderen Kommentarspalten werden hier wegen fehlender Englischkenntnisse kaum gross auftauchen, hoffentlich.