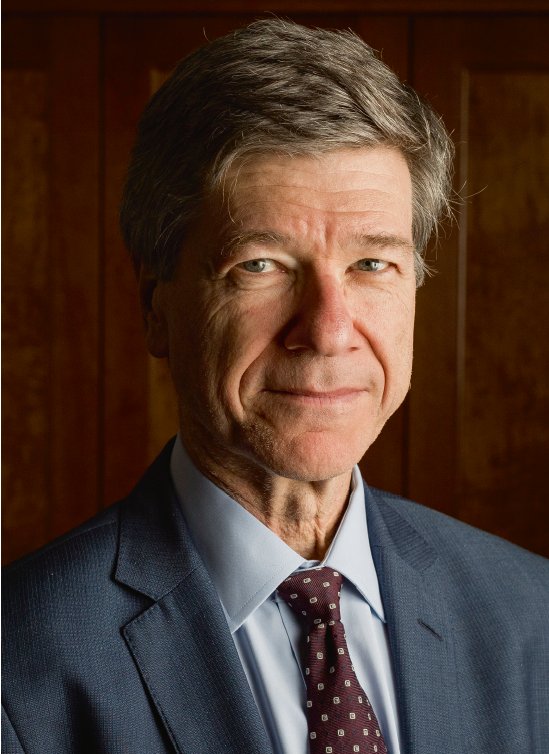

Columbia University Professor Jeffrey Sachs has decades of experience in crisis management. He played a leading role in advising the Kremlin's economic policy in the early 1990s. In Russia, he played a key role in the transition to a market economy in the early 1990s, as an advisor to then-President Boris Yeltsin. When Yeltsin announced the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the American economist was present in the Kremlin.

Those were extraordinary days, Sachs later said in an interview. They were not only exciting and promising, but also turbulent and deeply disturbing. He recommended shock therapy to the former communist countries for their transformation to market economies. Later, he applied his expertise to the fight against extreme poverty in Africa.

In his interview with Die Weltwoche, he explains what an economically rational environmental policy would look like. He also is making headlines for warning of the danger of escalation in the Ukraine war.

Weltwoche: You are urging a diplomatic solution in the Ukraine war, but there seems to be nobody around who would be able to negotiate a cease fire or even peace.

Sachs: The main responsibilities rest with [United States President Joe] Biden and [Russian President Vladimir] Putin. To a large extent, this is a proxy war between the US and Russia.

Weltwoche: What about Russia’s invasion?

Sachs: As much as many American politicians don’t want to hear it, Putin’s warning about NATO enlargement was both real and apt. Russia does not want a heavily armed NATO military on its borders. This position should be respected by the West. This would be the first step towards peace. When President Biden was asked about meeting Putin at the G20, Biden said, “Why should I meet with that person?” Biden, to my mind, misunderstands his job. His job is to try to use diplomacy to end the war.

Weltwoche: And what did Putin say about meeting Biden?

Sachs: I don’t know what Putin said, but I do know what Russians have been saying. They want negotiations.

Weltwoche: Putin was even avoiding the G20 meeting in Indonesia.

Sachs: Putin declined to go to the G20 after Biden ruled out a meeting with Putin. The whole situation is absurd, like children in a schoolyard, but in this case with thousands of nuclear warheads and a massive war raging in Ukraine.

I am of the school of John F. Kennedy, who said famously in his inaugural address, “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” So, I think that when you have a threat like we have right now, this is the right time to sit down and meet. In a diplomatic solution, no party gets everything it wants. Putin would not get to restore the Russian empire, and Ukraine would not get to join NATO, and the United States would be forced to accept the limits of its power in a multipolar world, by not putting its bases into Ukraine. If we don’t follow a diplomatic course, the threat is the ongoing destruction of Ukraine. Sure, Ukraine has won a major victory with Russia’s retreat from Kherson, but the next battle might go the other way with a massive destruction of Ukraine’s infrastructure.

Weltwoche: Western weapons enable Ukraine to defend itself.

Sachs: Correct. But it also leads to a spiral of escalation that could end up in a nuclear war. In the meantime, Ukraine continues to face massive death and destruction.

Weltwoche: After the Nord Stream leaks, you were pointing fingers at the United States and Poland. Actually there was no proof, at that time, and we still don’t know who caused the leak.

Sachs: I said that involvement of those two countries was likely. But, believe me, it was most likely the US, perhaps together with the UK or other allies.

Weltwoche: What kind of proof do you have to make this grave accusation?

Sachs: The evidence is staring us in the face. President Biden said on February 7th, in an interview that if Russia invades Ukraine, that’s the end of the Nord Stream Pipeline. The reporter was incredulous and said, “What do you mean, Mr President?” The pipeline belongs not only to German and Dutch companies, and mainly to Russia. Whereas the president reiterated (I’m paraphrasing), “Believe me. We have our ways.”

Weltwoche: Do you consider this a proof?

Sachs: I consider it evidence. There was another statement by the former Polish foreign minister, who twittered after the leak was discovered, “Thank you to the United States.”

Weltwoche: You must have seen that he deleted his tweet very fast.

Sachs: That is correct. So, you use your judgment. I'll use my judgment. But may I remind you that the US secretary of state said, after the fact, that the destruction of the pipeline is a tremendous opportunity to wean Europe off of Russian energy. I also remind you that the United States has opposed the pipeline all along. It even threatened its destruction. But I will ask you, since you’re a journalist, “Where are the media asking Sweden about its investigation?”

Weltwoche: What do you allude to?

Sachs: Why is it that the Swedes have done an investigation and are not sharing the results with Germany and Denmark? Isn’t that shocking? Why is it that a German member of the Bundestag, when she asked the government what happened, was told by the government that this is a national security issue, and therefore we are not going to tell you.

Weltwoche: You are talking about to Sahra Wagenknecht from Die Linke?

Sachs: Yes. So, I find this all absurd. Frankly, the evidence, in my opinion, points to the United States as the culprit. We should have a proper accounting of this. There were also media reports that may or may not be true that there was a CIA warning in advance to Germany about the coming destruction of the pipeline. So, these are the kinds of things that the mainstream media should be looking at.

Weltwoche: Couldn’t it be that Russia has an interest in destroying the pipeline, because Putin wants to punish Europe?

Sachs: Well, I think that’s absurd.

Weltwoche: Why?

Sachs: Since Russia wants leverage and bargaining power, the idea that it blew up its own pipeline does not make sense. Russia could “punish” Europe, as you put it, by turning off the gas without blowing up its own pipeline. By blowing up the pipeline, Russia would lose leverage, not gain it.

Weltwoche: You were chair of the COVID-19 commission for the medical journal the Lancet. As a result of your study you are asking intriguing questions about the origins of SARS-CoV-2.

Sachs: I am pretty convinced that the SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, came out of US-funded biotechnology. We know that the United States National Institutes of Health blocked any objective investigation of that issue, starting in the first days of February 2020. The failure of the US government to investigate is irrefutable. US-funded manipulation of coronaviruses was underway in the years leading up to the outbreak of the virus.

Weltwoche: Why would the researchers do this?

Sachs: Their aim was to look at the spillover potential of SARS-like viruses and, perhaps, to develop vaccines. What we know is that very dangerous research was underway and that there has not been a proper investigation by the US.

Weltwoche: So you don’t buy the theory that the virus could have escaped in a laboratory in China or in the wet market of Wuhan?

Sachs: All of these are possible. What I have called for, and what the Lancet Commission called for, is an independent, scientific, transparent investigation of those possibilities. It did not happen, so far.

Weltwoche: You are director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and attended the UN climate conference, COP 27, in Egypt. What was achieved at the conference?

Sachs: The COP is two things: formal inter-governmental negotiations plus global networking and brainstorming on climate solutions. The brainstorming side is very dynamic. There is a remarkable global cooperation of academics, businesses, cities, civil society organizations, academics, and others sharing very extensive, deep, and innovative ideas. It is very impressive.

Weltwoche: Of course, but it is not action oriented.

Sachs: It is action oriented, but it also needs government policy to work properly. The intergovernmental negotiations are indeed the laggard part of the process. Many governments are not yet doing what they need to do in policies, plans, public investments, and financing.

Weltwoche: Where does that leave the world?

Sachs: We know that the average temperature on the planet is higher than in any sustained period of the last 10,000 years, now. Therefore, we should decarbonize the global energy system by mid-century. This is the most important single step. The second most important single step is to end the rampant destruction of the rain forests and other land degradation.

Weltwoche: As an economist, I am asking you: Which policy is best suited to achieve a sustainable development? Laws or economic incentives?

Sachs: Both, of course, and this is what is needed and what is agreed to by the 196 signatories of the Paris agreement reached in December 2015. But the cooperation is too low, the vested interests of the fossil fuel sector is too high, and the governments too short-sighted. And, so, we are not getting the pace of policy change we would urgently need. The UN reported, end of October, that the best prediction of the Earth’s temperature at the end of the century is 2.6 degrees above the pre-industrial temperature. This is way out of the range that was agreed to in the Paris agreement and extremely dangerous.

Weltwoche: There is another danger — that of a bureaucratic bloat in the name of ecology.

Sachs: We already have an energy bureaucracy, but it is for fossil fuels. If you look at how Switzerland operates, which was a pioneer of hydro power, this goes back to state regulation well over a century. That the energy system being regulated is not anything new.

Weltwoche: This sound like pleading for strengthening a green bureaucracy.

Sachs: There is and will be a mixed and regulated system — part market, part state. There’s nothing new about that. This is what we’re going to have with a zero-carbon energy system, too. But let me also say this: There’s no place for a great power confrontation in this world if we’re going to solve this absolutely rapidly deteriorating environmental crisis.

Weltwoche: Besides the war in Ukraine, there is another friction — the one between the West and China. As with Russia, there is the danger of economic dependence. Could that be the end of globalization?

Sachs: Globalization has been part of human history throughout history. Certainly, for the last 500 years, we’ve been globally interdependent, and we will remain so. So, globalization is by no means ending. It’s in many ways intensifying, of course, in the digital age.

Weltwoche: Economic dependence can be a boomerang, as Europe is witnessing, now, in the energy supply from Russia.

Sachs: I find this comparison very strange. Of course we’re interdependent, but the United States is having a neurotic complex about China right now. This is really a kind of defensive reaction that is coming from the fact that the West doesn’t rule the whole show anymore. The center of gravity, where economic production takes place, is moving eastward towards Asia. That has been underway since the end of World War Two, actually, and especially since 1980. But that’s for a simple reason: 60% of the world population is in Asia. So, what was very unusual is that 60% of the world population would be in Asia, but only 20% of the world output was in Asia, as of 1950. But Asia’s economic growth, to my mind, is not only a natural process but a highly desirable process. It means that Asian countries are escaping from poverty.

Weltwoche: So, you welcome the fact that Western economies are on the losing side right now?

Sachs: It’s a funny thing to call that the losing side in economics. Asia’s escape from poverty is not the West’s loss. We economists think of mutual gains from trade. As a development economist, I think that development is a good thing when poor countries become less poor. I don’t consider it a loss for rich countries. So, I don’t view China’s progress as a Western loss.

Weltwoche: Extreme poverty in the Southern Hemisphere prompts migration to richer countries. What would be the solution to stop this?

Sachs: The solution is to insure a viable economy in all parts of the world.

Weltwoche: Africa has lots of resources, like the Middle East, but African countries remain poor and Gulf countries are among the wealthiest in the world. What are African governments doing wrong?

Sachs: It’s important to avoid oversimplified comparisons. The most important thing for Africa, today, is investment in education, health, and infrastructure, including electrification, transport, water, sanitation, and digital development. This is how China developed rapidly in the last forty years.

Weltwoche: One of the problems with Africa is that investments don’t trickle down to the population, meaning they stay with corrupt leaders.

Sachs: With all respect, it’s a little bit more complicated than that. I would urge people to read my books on this topic. Africa can certainly achieve rapid economic growth by investing in education, health, infrastructure, and business development. In fact, I’m optimistic that it will do so in the coming years, especially if the international financial architecture is adjusted so that more global saving flows to finance the investments in sustainable development.

Sie müssen sich anmelden, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Noch kein Kommentar-Konto? Hier kostenlos registrieren.

Mr. Sachs misunderstands Mr.Biden. This war isn't a mistake. He worked for the war and he wants and needs the war. It is a terrible thing, but making peace with Russia is not the game of Mr. Biden and Mr. Obama.

Sehr interessant!!

A great interview that survives silly questions with intelligent answers from someone in the know.

Couldn't agree more. Just bear in mind that Weltwoche plays the part of the non-specialist reader. But, with an interviewee of Dr Sachs' calibre I would have expected wider questions and not the endless harping on about minor issues such as North Stream 2.