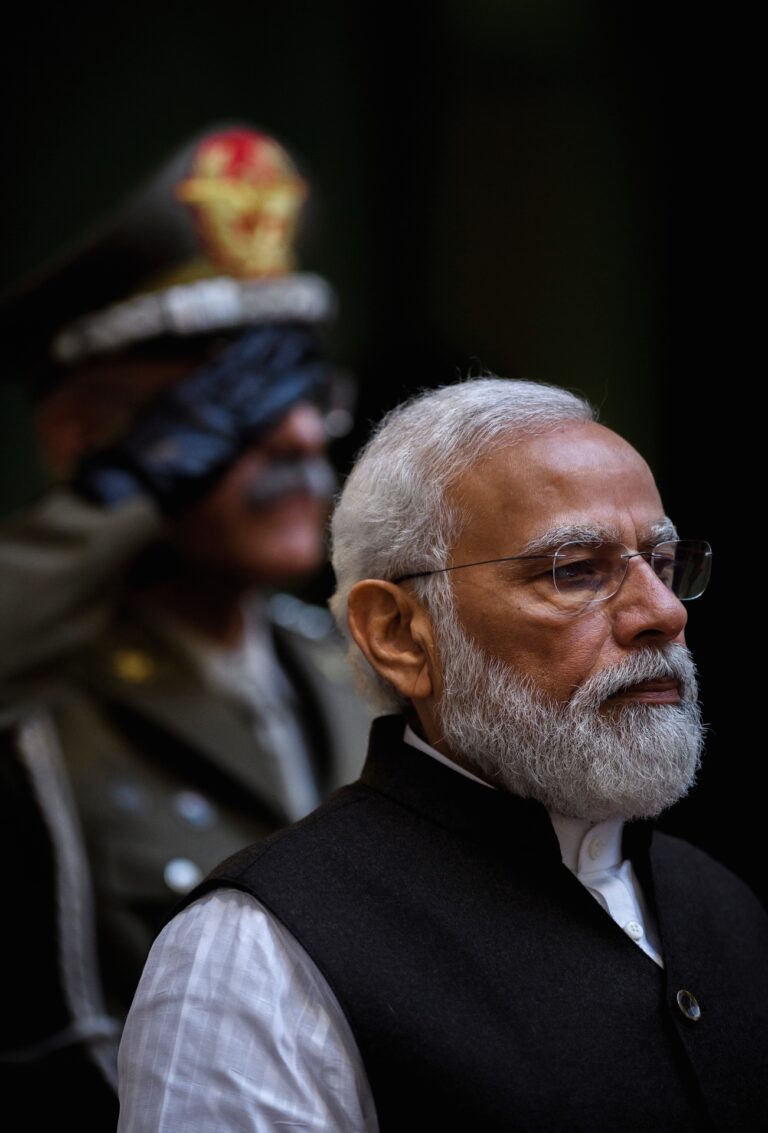

One assumes that Pope Francis has never had sex. The same goes for Tenzin Gyatsu, the 14th Dalai Lama. But they are religious leaders. Non-religious celibates, often high achievers, such as Sir Isaac Newton and Nikola Tesla are much rarer. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, who will have been in office for ten years in May, falls into this latter group; he has never had sex and he is not a religious figure. Or is he?

Remarkably for a leader in the current age, Modi’s background is murky to say the least. Born in Vadnagar, in the north-eastern state of Gujerat, he was the son of a grocer. His father sold tea or rather chai. By some accounts Modi, as a youngster, was a station platform Chai Wallah – a dispenser of impossibly sweet, milky tea to travellers. Academic achievements at school were modest but he excelled at acting - a useful skill for a budding politician. At the age of eight Modi had the transformational moment of his life - his introduction to the National Volunteer Organisation, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The RSS is a super Hindu spiritual and paramilitary organisation which operates throughout India. It has 5-6m members. Millions attend its 59,000 shakhas, daily branch meetings. Its political influence within the ruling BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) is such that apart from Modi, its members include 24 state leaders. Its quasi-religious leaders, pracharaks, are required to be celibate – ergo Modi’s sexual abstinence.

If the start of Modi’s training with the RSS was a seminal experience, the next moment of drama in his life is even harder to understand. At the age of 18 Modi’s parents, in the Indian tradition, arranged his marriage. Shortly thereafter Modi left home and abandoned his wife to spend the next few years travelling around northern India visiting ashrams (Hindu monasteries). Then in 1970 Modi went to work in his uncle’s canteen at the Gujerat State Road Transportation Corporation. Thereafter he worked his way up the ranks of first the RSS and then the BJP, becoming Chief Minister of Gujerat in 2001.

Altogether, Modi spent less than three months with his wife over four decades. It is not even clear whether he has even met her since 1970. The marriage was never consummated. It was a sensational ‘non-sex scandal’ when in 2014 shortly before the Lok Sabha (lower house) elections that elevated him the prime ministership, Modi fessed up to being married. The Congress Party led by Rahul Gandhi, Indira’s son, tried to make political capital out of this disclosure; given the Gandhi family’s lurid sexual history it might have been a story best left alone.

For many Indians the fact that Modi is a vegetarian teetotaller and celibate to boot is a plus not a minus. India’s great independence leader, Mahatma Gandhi, having sired four children declared himself celibate when he was 37. Though I doubt whether Modi, like Gandhi, has tested his willpower by sleeping naked in bed with underage young girls.

Gandhi overdid the pretence of being a fakir (a holy man who has given up all possessions); his rich patrons kept him in funds and the Indian poet Sarojini Naidu even joked that it cost a fortune to keep him in poverty. The same could be said of the meticulously dressed Modi who lives in the luxurious, Lutyens’s-built colonial governor’s house in New Delhi. Unlike Argentina’s new president Javier Milei who flies commercial, Modi uses his customised Boeing 777.

Modi, a known technophile, cultivates his ascetic image through television, his website and extensive use of Elon Musk’s social media platform X. Above all Modi has developed his cult status through his monthly Mann ki Baat (Talking from the Heart) radio shows in which he delivers homilies about cooking, water conservation, schoolwork etc. With a regular audience of 230m people the show is a phenomenon. At the same time, he can deliver brilliant one-liners, and cutting ad hominin attacks on his political opponents.

Given his RSS affiliation, Modi retains a surprisingly large following within the Muslim community. This, despite being accused in 2002 of complicity with the RSS for anti-Muslim riots which led to the death of as many as 2000 people, mostly Muslims. A febrile inter-communal crisis led to 150,000 people fleeing to refugee camps. Though Modi’s guilt has never been proven, he was barred entry to the US for a decade.

For RSS’s enemies it is an ultra-right wing nationalist organisation not unlike Japan’s ruling Liberal Democrat-supported Nippon Kaigi which promotes the state Shinto religion. Rakesh Sinha, an RSS follower, and a BJP member of India’s upper house openly admits that there is ‘consistent psychological indoctrination of RSS cadres.’ Despite his record of racial harmony in government, to the international liberal elite he remains a toxic figure.

To leftists, the mere mention of the RSS generally leads to a derangement not dissimilar to that for Donald Trump; for them Modi is simply a Muslim hating RSS stooge whose personality cult has taken over the BJP. Despite his record of racial harmony as prime minister, to the international liberal elite he remains a toxic figure. Perhaps surprisingly the left leaning Mark Tully, the BBC’s legendary long serving correspondent in New Delhi is more nuanced. He believes that ‘The Media… should stop blind criticism of RSS.’

In India all politicians, regardless of party, must deal with the inequalities of the caste system and the poor. My own experience of four years living in Bombay was that identity of caste and state was much more important than political affiliation. Indeed, after the collapse of India’s main trading partner, the Soviet Union, in 1991, the economic ideologies of the formerly socialist Congress Party and the BJP were barely distinguishable.

In 2005, when a BBC interviewer disapprovingly asked why India had abandoned socialism, Congress Party big hitter, P Chidambaram, bluntly replied, ‘socialist means do not deliver. We tried that for thirty years.’ At that time, I used to meet young Congress Party technocrats in the Indian government, such as Jairam Ramesh, (later a minister for the environment), who were as enthusiastic about structural economic reform as the young turks I knew who surrounded Margaret Thatcher when she came to power.

Modi became the BJP leader through his perceived astute management of Gujerat’s economy. India with its 28 states and 1.4m population has been a bigger task. Over the last decade he has made India fit for economic take-off. He has given emphasis to the upgrading of India’s previously decrepit infrastructure, including its highways, railways, water distribution, power supply and its banking system. As a result, India has become investable and is an increasingly attractive alternative to China. Foreign direct investment (FDI) into India rose from US$36bn when Modi came to office in 2014 to US$76bn in 2023.

No wonder countries are beating a path to India. Trade deal aspirants include the United Kingdom, Israel, New Zealand, Canada, Bangladesh, and Oman. When Modi came to power his priority was to complete trade and investment deals with ASEAN. Modi’s latest coup has been to complete a trade and economic partnership agreement with Switzerland as part of EFTA. After transitional periods customs duties on 95.3% of industrial products will be rescinded. Over time Switzerland will also gain duty free access for its agricultural products. Importantly protection of intellectual property rights will be enhanced. Similar economic access gained by Switzerland is now being sought by the European Union and other region economic groups in Africa, the middle east and central Asia.

Although India is increasingly courted by the US as an ally and bulwark against China, Modi has pursued a determinedly independent line. Despite calling for an end to the Russo-Ukraine War, Modi remains on good terms with Putin and Russia. Because of India’s increasing global importance, Modi was given a free pass by the west when he spurned their economic blockade of Russia.

In summary it is clear the Modi has become the most consequential leader in India’s history as an independent country. Comparatively Nehru, the founding father of the Indian nation, was a socialist blowhard who completely failed to make his country fit for the 20th Century let alone the 21st Century. His daughter and successor, Indira Gandhi, a neo-Marxist was worse. Some have argued that between them they caused an economic and humanitarian catastrophe as bad as Mao Zedong’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ which killed 30 -50m people.

Although it was a Congress prime minister, Narasimha Rao, who initiated the abandonment of India’s post-colonial Marxist economy, it is Modi who is pushing India forward to fulfil its potential as a great world power. After ten years he has laid the groundwork for this transformation. Whether he completes the job remains to be seen. But Modi, India’s celibate superhero, is in no doubt. As he recently declared ‘The work of these 10 years… this is a trailer, I have a long way to go’.

Indien verstehen leider nur wenige. (8 × bereist) Ich wünsche mir sehr, dass es sich kulturell und wirtschaftlich niemals dem Westen angleichen wird. Danke für diese ausführliche Abhandlung zu Modi