In early September of 2023, fourteen months before their next elections, Americans have been shocked to discover that Future Forward USA Action, a consortium of high-tech billionaires, was spending $13 million on television and online advertising to boost a presidential candidate’s fortunes of. More shocking than the size and early-ness of the expenditure, was the identity of the candidate. It was President Joe Biden. Future Forward has always liked Biden. Buoyed by large contributions from Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and now-disgraced crypto-currency impresario Sam Bankman-Fried, it spent about $150 million to get him elected president in 2020.

That shouldn’t be necessary now, since Biden is running unopposed for his party’s nomination. The huge publicity program can only mean one thing: The Democratic party’s most attentive funders are beginning to worry that Biden is in danger of losing the coming general election to his indicted rival Donald Trump. According to a recent CNN poll, both candidates have the same favorability rating: 35%. After two years of roaring inflation, 58 percent of Americans believe Biden has made the economy worse.

It may seem a mystery that the party clings to Biden in the first place. The reason has to do with the sea-change the party has undergone. Between the days of Thomas Jefferson and 1960s, the Democrats were a party of the unequal and agrarian South. When the Civil War ended in 1865, resentful Southern whites shunned the anti-slavery Republicans and deepened its attachment to the Democrats. The South became a collection of one-party states, all of them loyal to the Democrats. But the party also had a very different Northern wing, one that organized rising immigrants into blocs for securing political patronage. What united these disparate wings was a sense of exclusion from the conclaves of power. In the middle third of the 20th century, between the presidencies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, the Democratic party was as genuine a workingman’s party as the United States has ever known — but not a radical one, by mid-twentieth-century standards. It was driven to centrist positions by the illogic of its coalitions and by its sheer size. It sometimes won close to 70% of the seats in Congress.

The Democrats are not such a party any longer. In not much more than two generations it has become a party of financial and academic elites. This transformation happened in two steps: First the Democrats became a racial party. Then they became a plutocratic party.

When the country’s business and financial elites failed in the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s inspiration was to assemble a counter-elite out of the waves of European migrant groups — Germans, Irish, Italians, Poles, Jews, Greeks — who had arrived since the 1880s. A lot of them worked in factories; industrial unions became an arm of the party, as they did among European Social Democrats. Catholic churches were also central; Kennedy may have received 75 percent of the Catholic vote in the elections of 1960. Kennedy had broad appeal among patriots and anti-Communists, too, and was even somewhat hard-line on such questions: he was the only Senate Democrat to vote not to censure the radical anti-Communist Republican Joseph McCarthy in 1954.

The assassination of Kennedy in 1963 marked a turning point. By then there was no long a rough balance between the party’s Northern and Southern wings — the former were more numerous, more educated, and more influential than the latter. What the Southerners had was a stranglehold on congressional power, especially in the Senate. Kennedy’s successor Lyndon Johnson took it upon himself to solve the country’s race problem by integrating the institutions of the South. In 1964 he passed an ambitious Civil Rights Act by convincing voters it was what their martyred president would have wished. (Even though Kennedy had been lukewarm on civil rights for most of his presidency.) For a while after Kennedy’s death, Johnson framed most issues that way. “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long,” Johnson said in an address to Congress five days after the assassination. “And second, no act of ours could more fittingly continue the work of President Kennedy than the early passage of the tax bill for which he fought all this long year.”

The result was a realignment in American politics. In Blacks, Democrats gained a constituency of extraordinary loyalty, which persists to this day. In the four elections after the year 2000, black voters gave the party of civil rights 90, 88, 95, and 93 percent of their votes. But civil rights was an unresting crusade.Democrats kept seeking new constituencies that might accept this trade of special rights in exchange for extraordinary majorities. They promoted affirmative action in education and hiring, and forced the busing of children to distant districts to achieve racial balance in schools. These were enormously unpopular programs, but civil rights was a powerful tool for disrupting institutions and directly redistributing power of all kinds.

Democrats have become the party of those whose concerns had never been in the forefront of American political life until the 1960s—blacks, gays, and women—and of tens of millions of immigrants (and their offspring) who have arrived in the country since thenl. In diametric contradiction to what one would have expected from their sociologically very Catholic electorate in 1960, the Democrats became the pro-abortion party, and Republicans the anti-abortion one.

Republicans, meanwhile became the party of everyone else: practically everyone who had belonged Roosevelt’s mid-twentieth-century New Deal coalition, and practically everyone who had opposed it. Democrats struggled to regain the allegiance of non-rich white people. After World War II, Democrats had made a tradition of beginning every presidential season with a labor rally in Detroit’s Cadillac Square. That lasted until 1968, when presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey was too embarrassed by riots in Detroit’s nearby black neighborhoods to do that. In 1984, Ronald Reagan got more than twice as many votes among white people as his Democratic rival Walter Mondale. And by the end of Barack Obama’s time in office in 2016, race divided the parties more than anything else. Democrats, by 84 to 12 percent, thought racism was a bigger problem than political correctness. Republicans, by 80 to 17 percent, thought political correctness was a bigger problem than racism.

But something else happened. Democrats not only lost poor people. They gained rich people. In the mid-twentieth century Democrats had been the party of the “left,” of “planning,” of “progress” — a party that most university professors and administrators found most congenial. With de-industrialization and the rise of the high-tech industry in the 1980s, a lot of American wealth creation, and the management of American economic power, moved from the industrial-age factory to the post-industrial university. Elites of all kinds came to associate with Democrats, the news media above all. As the media critics Jack Shafer and Carter Doherty noted a decade ago, media jobs in the old days had been spread nationwide and linked to the political cultures of their diverse readerships. “The Sioux Falls Argus Leader is stuck in South Dakota just as the owners of hydroelectric plants in the Rockies are stuck where they are,” Shafer and Doherty pointed out. But 21st-century internet media jobs were not like that. Three quarters (73 percent) were either in the cities of the northeast and the West Coast, or in Chicago. Those places were rich and overwhelmingly Democratic: 90 percent of people working in the reconfigured news industry lived in a county that Democrats would win in the 2016 presidential election.

The Democratic party is a special one. There have been other center-left parties that have lost their working class orientation and, under the influence of their university wing, taken on elite members. The Socialist party in France made the transition in the 1980s, after François Mitterrand was elected president, focusing on cultural and even racial issues rather than delivering concrete improvements in living standards to workers. Tony Blair’s Labour party did the same after he came to power in 1997. Germany’s Social Democrats have been more immune than most to such a transformation. None of center-left parties in Europe have become the party of the ruling class and its retinue, the way the 21st-century Democrats have.

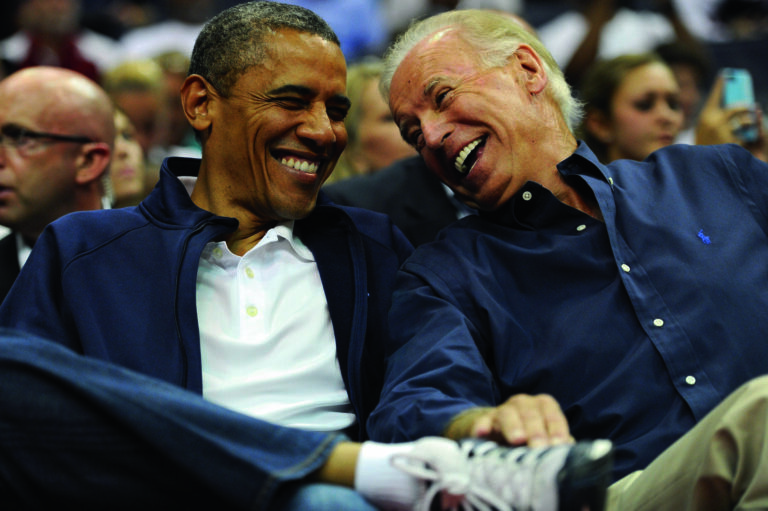

By the 2020 election, even running against a Republican incumbent, Joe Biden’s candidacy had the kind of enormous establishmentarian advantages that one associates with late nineteenth-century Western European bourgeoisies or late twentieth-century Eastern European oligarchies. Democrats ran the first billion-dollar presidential campaign in 2020, out-raising Donald Trump by about 60 percent. They funded a hundred-million-dollar Senate campaign in South Carolina and came close to that mark in Kentucky. By summer, Biden was outspending Trump on advertising by two-to-one nationwide, and by three-to-one in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Biden was a sort of Potemkin candidate – he claimed to speak for the white working class, much as Democratic politicians did when he was first elected to the Senate in 1972. But the party had changed, and his own rise to the presidency would only have been possible in the new era of identity politics and plutocracy. Party elites wanted Biden as the nominee, thinking he would have a better chance of beating Trump than the Socialist Bernie Sanders did. But in the “primary” elections and caucuses through which Democrats pick their nominees, voters showed no sign of feeling the same way.They consigned Biden to fourth place in Iowa, fifth place in New Hampshire, and a distant second in Nevada. Sanders topped all three.

It required the intervention of the party’s money men and its racial organizers to save Biden. The primary in South Carolina was the last place place they made their last stand. The party there is almost 60 percent Black and subject to influence by its senior figures. When Biden got the endorsement of 79-year-old black House Majority Whip James Clyburn, reportedly after promising to nominate a Black woman to the Supreme Court, the state fell into line.” The other non-socialist candidates then dropped out of the race. Biden won 10 of 14 states in the so-called Super Tuesday races a few days after. But in only five of them did his newly consolidated establishment candidacy outpoll the combined socialist vote of Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. It appeared the primary campaign might be over. A week later, there was no longer any “might” about it. By then, the U.S. had 1,000 coronavirus cases, and the dispute about the ideological direction of the party was buried.

Until now. That is why Biden needs the Future Forward billionaires to ride to his rescue again. He got extremely lucky last time. Democrats have reason to worry he will not be so lucky again.

Christopher Caldwell is a contributing editor at the Claremont Review of Books.