Retired United States Army Colonel Douglas Macgregor does not suffer fools. In the West’s efforts to assist the Ukrainians in repelling Russia’s invasion, he sees a motley crew. Once regarded a war hero, the Gulf War veteran is now denounced as a “Putin apologist” for his uncompromising criticism of what he regards as the West’s duplicity toward the old Cold War foe.

The 69-year-old strategist tells Die Weltwoche, “At this point, the notion that the Russians would negotiate with anybody about events in Ukraine is simply unrealistic.” More ominously for the Ukrainians, Macgregor believes their fight for territorial integrity is already lost. He dismisses glowing reports of Ukrainian tactical victories as a politically concocted “fiction.”

This is not the first time the battle hardened warrior has crossed swords with the foreign policy and military establishment. As an active duty officer, he took the extraordinary step of publishing a radical critique of the U.S. Army’s military readiness with his book, “Breaking the Phalanx.” Praised by the then-head of the Army, General Dennis Reiner, and later by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Macgregor’s public criticism was, nevertheless, viewed by many top brass as a shot across the bow. U.S. News and World Report observed, “The Army is showing it prefers generals who are good at bureaucratic gamesmanship to ones who can think innovatively on the battlefield.”

Years after serving as one of the top planners for NATO’s successful 1999 aerial bombing campaign of Kosovo to expel Yugoslavian forces, Macgregor found himself, once again, crosswise with official Washington. Appearing on Russian state television RT in 2014, the American colonel advocated for a plebiscite in Ukraine to allow Russians in Eastern Ukraine to decide whether their future was in Ukraine or Russia.

In the wake of President Biden’s announcement, last week, that that the U.S. plans to supply Ukraine with more advanced rocket systems and munitions, we turn to the foreign policy heretic for his provocatively contrarian views.

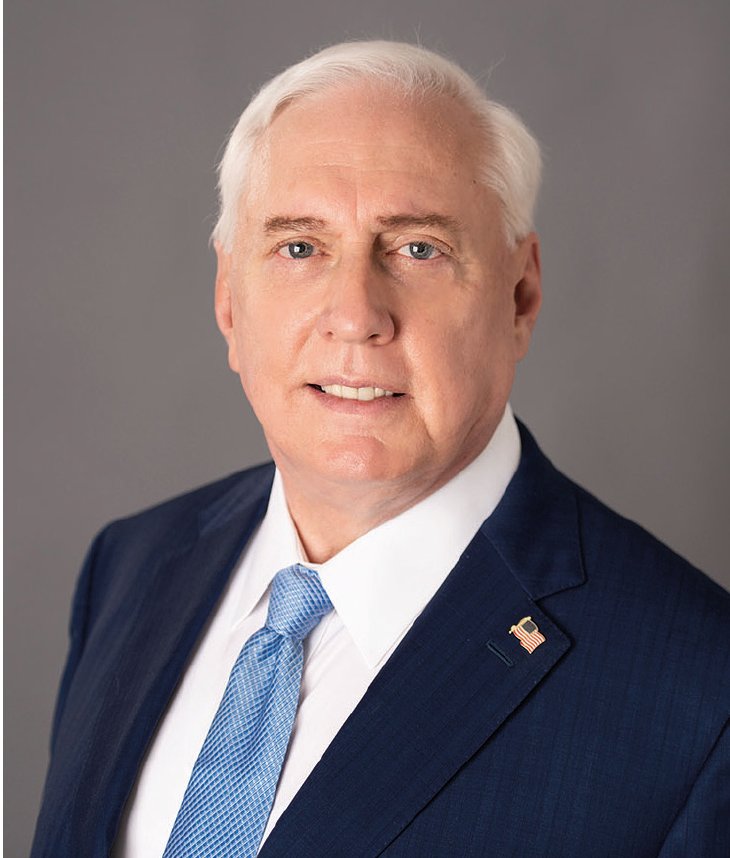

”The western unity you're seeing is a facade, at best”: Colonel Douglas Macgregor.

Weltwoche: Colonel Macgregor, could the American missile systems that President Joe Biden wants to deliver become a game changer in the war?

Doug Macgregor: No. These weapons are not going to have any significant impact whatsoever. First of all, this “High Mobility Artillery Rocket System” is a good system, but we are sending only four launchers. This is about as significant as sending four tanks. You don't have a significant impact with so few launchers. Keep something else in mind. It takes, on average, at least five weeks to train crew members on the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System. Unless we are sending American soldiers to operate these systems, it seems very unlikely to me that these systems are going to be placed into operation quickly and have any real utility at all.

Secondly, the 50-mile range is the outer limit of the system. I doubt that they would get any rockets close to the Russian border.

Then, finally, when the High Mobility Rocket System fires, it is visible from low Earth-orbiting satellites. That means, as soon as you fire a salvo of these rockets, the first thing that you absolutely must do is rapidly move to a new location. If you don't, you're going to be identified and destroyed by counter-battery fire.

If we've learned one thing from this current war, the Russians have excellent counter-battery fire capability. They have the radars, they have the links to the intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance assets in space, as well as overhead in the terrestrial environment. The bottom line is these four launchers are going to make absolutely no difference at all. It looks like a face-saving venture by the U.S. government to create the illusion that we've done something important for Ukrainians when, in fact, we haven't.

Weltwoche: In reaction to the announced deployment of US rocket systems, Russian Security Council Deputy Chairman, Dmitri Medvedev, said that "if, God forbid, these weapons are used against Russian territory, then our armed forces will have no other choice but to strike decision-making centers.” If the four launchers are going to make absolutely no difference on the battlefield, as you point out, then the Russians can easily relax, can’t they?

Macgregor: The Russians are simply reinforcing something that they actually made clear from the very beginning of this operation. If we begin to operate from neighboring NATO states and directly attacking Russian forces in Ukraine, they will view those neighboring states as co-belligerents. Right now, the state that is the assembly area for the distribution and projection of new equipment and assistance into Ukraine is Poland. It is not unreasonable for the Russians to say, “If these things come in from Poland and they actually hit Russia, we will strike Poland.”

Now, my point is that I think the people in Washington are acutely sensitive to this, more so than people think in Europe. As a result, it may have started out as a much larger infusion of rocket systems. I think that they suddenly scaled back.

Weltwoche: You called the deployment of those few artillery rocket systems “a face-saving venture” by the Biden government. In a recent interview with Tucker Carlson [on the Fox News Channel], you went further, saying that the U.S. administration “really doesn’t want to admit that this war has been lost a long time ago.” When was the war lost, in your view?

Macgregor: I think it was lost mid-to-late March. The reason is that the Russians had very limited and discrete goals when they began this operation. First of all, they said they wanted neutrality for Ukraine. They wanted autonomy for the so-called “Donbas Republics,” which are all Russian speaking. Under that, they wanted equal rights for Russian citizens of Ukraine to be allowed to speak Russian, to be allowed to live as they see fit. Then, finally, recognition that Crimea is legitimately part of Russia. Those were the three basic goals or objectives. The Russians made it very clear, from the moment they moved into Ukraine, that they wanted a negotiated settlement.

When they finally moved in, they did not move along three or four axes where they would concentrate the striking power of their force. They, in fact, dissipated their combat power. In other words, along a 500-mile front, they moved in at several different locations with the goal of avoiding damage to infrastructure, avoiding collateral damage to people, to human beings. They simply did not want to kill very many people when they went in, and they wanted to give people an opportunity to join them, including Ukrainian forces who didn't want to fight. That didn't work very well.

Weltwoche: Why didn’t it work?

Macgregor: Because, as soon as the Russians admitted that they were only entering Ukraine for the purpose of neutralizing or destroying the Ukrainian threat to Russia and that they would withdraw once they arrived at some sort of negotiated settlement, the majority of Russian speakers (millions of them in Eastern Ukraine) said it's unrealistic for them to join the Russians because, as soon as the Russians were gone, Ukrainian secret police would show up and murder them and their families. Thus, they were not helping.

All of that was evident by the 16th to the 23rd of March. It became clear that the Ukrainians were not negotiating in good faith. The Russians intelligence network discovered that we (Americans) and our friends in London were urging the Ukrainians to fight on and promising Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy that we would give him whatever he needed to win. At the same time, we were creating this fiction that the Ukrainian forces were actually having great success against the Russians when, in fact, the Russians were crushing them and there were very few examples of so-called “Ukrainian tactical success.”

I think, at that point, the Russians said, “Well, the game is up. We're not going to get any cooperation out the West. The United States has effectively said they want to grind us into the dust.” They changed their operations. They stopped fighting for particular cities. They said, “We'll simply circle these places to the extent that we can. While we cut those off or isolate them, we will then focus on major concentrations of Ukrainian forces.”

Those large concentrations were always in the Donbas, and it has taken another three or four weeks to re-concentrate Russian forces to execute that mission and achieve that objective. I think what we need to understand is that, at this point, the notion that the Russians would negotiate with anybody about events in Ukraine is simply unrealistic.

Weltwoche: There are several points that I don't want to leave unchallenged. You say that the Russians "simply did not want to kill very many people when they went in.” The countless attacks on civilian targets and the bombardment of cities like Mariupol, which the Red Cross described as "apocalyptic," prove that the Russians are not holding back from killing children, women, and the elderly indiscriminately. In your enumeration of Putin's war aims, you also forget to mention that Putin's openly declared intention was to decapitate the government in Ukraine, which he falsely claimed was run by fascists. He obviously did not achieve that goal. Further, you claim that "the Russians were crushing” Ukrainian forces. In truth, the Ukrainians defended themselves with determination, from day one. The Russian troops were forced to retreat and reorganize in the east of Ukraine. Finally, it is important to keep one fact clearly in mind: Putin attacked a sovereign state under threat of using nuclear weapons. There has never been a similar blatant violation of international law in the modern history of Europe.

Macgregor: I think this business about international law needs to be re-examined. The French, the British, and the Americans all intervened in Libya and, essentially, destroyed the government there, decimated the society, and created chaos which continues to persist to this day. There is no stability in Libya, and no one seems to have raised any issues about international law.

We (Americans) intervened in Syria after having intervened in Iraq where we created chaos of the structure and on a scale that is, certainly, greater, if not much larger, than Ukraine. No one seems to have raised any issues about international law. We have launched all sorts of strikes and raids all over the world at our discretion against anyone we thought was the enemy, effectively assassinating with aircraft or unmanned systems or missiles anyone in Africa, the Middle East, or even in South Asia, who we deemed a threat. No one seems to have raised any issues about international law.

I think if you're going to talk about international law, your audience isn't going to be very receptive. They see international laws applying on a very exceptional basis to those that the United States, Britain, and France don't like.

Weltwoche: So, in your eyes, there is no reason to criticize Putin for the attack on Ukraine, even though Ukraine had not taken a single step of aggression against Russia?

Macgregor: The Ukrainians had been very straightforward about their determination to re-conquer the Donbas and then, subsequently, to regain control through conquest of Crimea. If you're a Russian and you're looking at that — and you're seeing the enormous buildup of weapons and equipment in Ukraine, particularly Eastern Ukraine, and you reckon that the United States at some point is going to move strike assets in terms of medium, intermediate-range missiles into Eastern Ukraine that could reach very important targets in Russia in a very short period of time — you make the decision to go in or sit and do nothing.

The calculus [for Russia] was very simple: “If we do nothing, what happens? Well, the situation in Ukraine becomes more and more dangerous with each passing month and year to Russia. If we do something, we'll be condemned by everyone, but we can at least destroy the threat.”

Ultimately, they came down on the second option. It's not the best, but it was the only one they saw because they saw no evidence that we or anyone else was going to listen to them.

Weltwoche: One more point. You say, “It became clear that the Ukrainians were not negotiating in good faith.” Let’s suppose Switzerland or America was attacked. Would you negotiate with the aggressor “in good faith” after he has already seized large parts of your sovereign country?

Macgregor: Now, as far as negotiating in good faith, if you are fighting a major enemy and your back is against the wall, yes, you negotiate, and you negotiate seriously because if you do not, you risk total destruction. Now, the good news for Ukraine was that there was never any interest in Russia in the total destruction of Ukraine. There was no interest, initially, in capturing, permanently occupying any territory. That has changed.

The Russians now see no alternative but to remain where they are in Eastern Ukraine — to annex or incorporate those territories in some fashion into Russia, to hold the ports in the areas from which Ukrainians would normally export grain, and to retain control of 90% of Ukraine's industrial base, which was formally Russian, anyway.

Weltwoche: Let's focus on the United States, the leading western power. President Biden has been sending mixed and contradictory messages for weeks. In his recent New York Times op-ed, Biden wrote, “As much as I disagree with Mr Putin, and find his actions an outrage, the United States will not try to bring about his ouster in Moscow,” Back in March, Biden declared that Putin “cannot remain in power.” Can the U.S. government be taken seriously?

Macgregor: The easy answer is “no.” But I think the United States has been confused for a long time. This government is probably more confused than almost any other we've had, but we don't have a clear, unambiguous, strategic framework from which we operate. There is no clear, unambiguous, end state for anything that we embark upon.

Now, in Ukraine, we tried to vilify and demonize Mr. Putin as some sort of evil dictator and characterize him as worthy of removal. Well, that hasn't worked very well. There's no chance of Mr. Putin being removed by an internal coup or any other force inside of Russia. Mr. Putin's approval ratings inside of Russia are well over 85%. He has enormous support in the country for doing what he's doing in Ukraine — not because Russians hate Ukrainians, because they don't, but because the Russians agreed with him that Russia, itself, was confronting increasingly what could become, in the near term, an existential threat to the Russian state and the Russian people.

Now, the question is, “What is the United States' strategic objective in Ukraine? What do you want the situation to look like when the fighting ends?” That question was never asked, and it's never been asked in any of the interventions we've conducted over the last 30, 40, 50 years.

Weltwoche: Not too long ago, French President Emmanuel Macron called NATO, "brain dead." Now, the alliance has been given a new lease on life in the wake of the Ukraine war. Even the neutral countries of Sweden and Finland want to join the alliance. That can't have been Putin's intention, can it?

Macgregor: I think that NATO is weaker than ever. The unity you're seeing is a facade, at best. Macron was absolutely right, and he was not the first to make those statements. The United States does not have allies in Europe. It has military dependencies. There is one country in Europe that is capable of fielding significant military power and dominating the scene if necessary, and that is Germany. Germany, today, is what it was before World War II and World War I. It is the dominant power, regional power, and, to a large extent, an international power.

Weltwoche: Economically speaking...

Macgregor: Yes. But it could become everything else overnight if it chose to do so. Nothing, fundamentally, has changed in that regard.

On Sweden and Finland, I don’t think they are going to join, because I don't see much evidence that Turkey (which objects to granting membership to the two) is going to change its position.

I have watched NATO from the inside and have seen it being extremely dysfunctional. Over and over again, the Europeans were never able to agree that any one European state would take the lead on much of anything. They never built the capabilities that were necessary to defend European interests. So, they defaulted to America's enormous investment in command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Europe was effectively defenseless without the United States.

A series of American presidents have enjoyed that condition because we suffer in the United States from what I would call, “national narcissism.” It is flattering to us to think of ourselves as this great imperial power that protects and dominates everyone. I think that's going to change because, quite frankly, we don't have the funds or the resources to maintain this level of military investment in perpetuity. In fact, I think we're coming to the end of it. When we hit the end of it, you're going to see a massive withdrawal of U.S. forces from all over the world.

Weltwoche: Russia has been saying for years that it sees NATO’s enlargement as an existential threat. If the alliance is as weak as you say, Russia has nothing to fear, has it?

Macgregor: Russia is not afraid of the Europeans and never was. Russia always saw the European states as entirely subservient to, and dependent upon, Washington. NATO is the United States-led alliance. As long as we are seen as the dominant power in Europe and unambiguously hostile to Russia, then, yes, Russia is going to view what happens under the broad title of “NATO” as an existential threat to Russia.

Zu kompliziert was der Mann sagt? Diser Krieg wird mit einem Waffenstillstand enden. Putin wird genau das erhalten was er vor Kriegsbeginn täglich gefordert hat: zwei Provinzen und ukrainische Neutralität. Der Krieg, die Toten und die Kosten wurden von dem einzigen Land gefordert, die an diesem Krieg verdient haben, die USA! Es sind die demokratisch gewählten, aber inkompetenten und korrupten Regierungen Westeuropas, die dies zugelassen haben und bezahlen. Erfreulicherweise nicht die Schweiz...

Ausgezeichnetes Interview mit Colonel McGregor. Er sieht die Lage unabhängig. Leider stellt der Interviewer, oft nicht die richtigen Fragen, weil er im Gegensatz zu seinem Gast, voll auf das westliche Narrativ abfährt. Ein Blick in den Antispiegel, RT, Alina Lipp, Lancaster, Novoviso, etc. würde ihn über beide Seiten aufklären. Was die Zerstörungen in Mariupol betrifft, war das die Ukraine selbst, die Zivilgebäude mit Zivilisten als Schutzschild missbrauchte. Das sind echte Kriegsverbrechen!

Die Ukraine wird mit Altwaffen aufmilitarisiert und der Westen, angeführt von Links- und Grünkoalitionen, jubelt einem aussichtslosen Krieg zu. Auf Kosten der ukrainischen Bevölkerung. Dass da auch noch die Schweiz mitmacht ist eine Schande. Ihre Neutralität wird nicht mehr anerkannt und so kann sie auch nichts mehr zu einem Frieden beitragen. Sie ist Kriegspartei.