The New Cold War

The West must stand up to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, or it will be doomed. Historian Niall Ferguson on how to win the epic confrontation with the “Axis of Ill Will.”

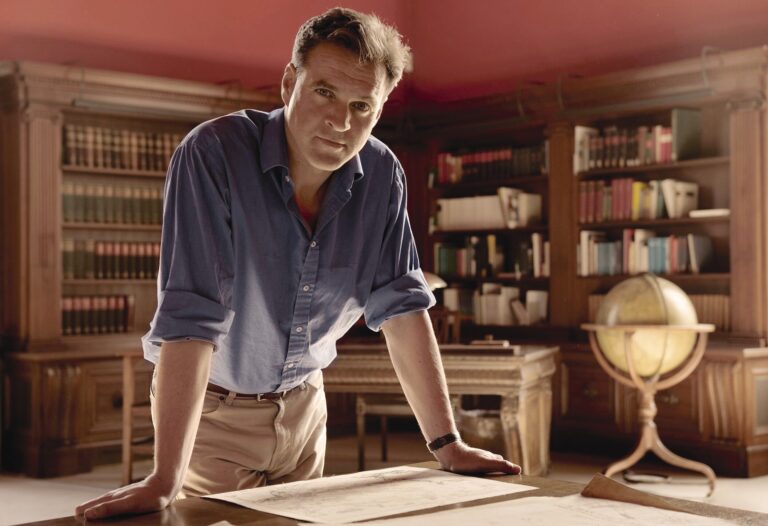

Superlatives should be used sparingly, but when discussing historian Niall Ferguson, they become unavoidable. The Telegraph describes the public intellectual as “a maverick Oxford don who is far too young, successful and right-wing to enjoy the unanimous approval of his colleagues.”

The author of more than a dozen acclaimed tomes, the 60-year-old Scottish American ranks among the most important contemporary thinkers.

Ferguson first rose to prominence with his works on British and US imperialism. In them, he provocatively recast the British Empire as one of the world’s greatest modernizing forces that continues to benefit mankind to this day.

Ferguson and his wife, the Somali-born human rights activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, are a veritable conservative power couple. Hirsi Ali is known for her warnings against the mass importation of Muslim migrants into Western societies and the naive multiculturalists who invite them.

A Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and co-founder of the University of Austin, Ferguson is currently at work on the second volume of his biography of Henry Kissinger. He takes a break from this massive project to discuss the epochal topic of our time: the new Cold War.

Weltwoche: For quite some time, you have argued that we are in a new Cold War. This time, however, the main adversary is headquartered not in Moscow, but in Beijing. You warn that this Cold War is escalating faster than the first.

Ferguson: Yes, I’ve been talking about Cold War II since 2018. It’s now, I think, more widely recognized. In fact, there are books being written and published about it. I think I was first to realize that we were now in a Cold War, and China had taken the place of the Soviet Union.

Weltwoche: In a recent article for Bloomberg, you write that, “to understand what is at stake with this Cold War, just read the Lord of the Rings.” You’re referring to Tolkien’s “forces of darkness.” Who are those forces? Who is this “Axis of Ill Will,” as you call it?

Ferguson: The “Axis of Ill Will,” which I prefer to “Axis of Evil” just because “Axis of Evil” was a fake axis; there was no axis in 2002. [“Axis of Evil”—referring to Iran, North Korea, and Iraq—was first used by US President George W. Bush in his State of the Union address five months after 9/11]. The “Axis of Ill Will” is essentially the People’s Republic of China and it’s no-limits partnership with Russia. There’s also Iran. North Korea is involved too. One might add Venezuela to the list, but it’s a minor player.

Weltwoche. What are they up to?

Ferguson: Well, despite having almost nothing in common, ideologically, they have a common objective, which is to end American primacy and the primacy of democracy and the free market economy as the ideals to which we would like all countries to aspire. I think this was very obvious when, just before the invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping met and spoke of a no limits partnership.

The green light was effectively given in Beijing for the invasion of Ukraine. China has provided substantial economic support to Russia, ever since the invasion. Indeed, without China’s exports to Russia, it’s hard to see how the Russian war economy would keep going. Iran has also supplied drones and missiles to the Russians. North Korea has supplied ammunition. We can see, in Ukraine, that they work together.

They also work together in the Middle East, because Russia is certainly going to increase Iran’s air defense systems. China buys nearly all of Iran’s oil, which is supposed to be under US sanctions. I could go on, but you get the general idea. You can’t take these conflicts separately and pretend that one is different from the other. You cannot, as some Republicans say, ignore Ukraine and leave it to Putin and focus on Taiwan or on Israel. That’s not realistic. You have to recognize that they’re interconnected.

Weltwoche: Is it just the four powers that you mentioned? Russia, Iran, China, and North Korea? It seems that they get support from the BRICS states, such as India, Brazil, and South Africa. How do they position themselves in that new Cold War?

Ferguson: In the first Cold War, there were a substantial number of states that were non-aligned, including India and Yugoslavia, and Egypt for a time. On close inspection, they weren’t really non-aligned. They were closer to the Soviet side. In the same way, countries in the BRICS lean towards China. Brazil is a good example of this. President Lula has been notably uncritical of China and sympathetic to the Russian side. South Africa is similar.

Some of this is corruption, and some of it is ideological alignment. There are these, let’s call them fellow travelers, who aren’t directly contributing to, say, the Russian war effort, but they are sympathetic. Sometimes, they call themselves the BRICS, and sometimes they call themselves the Global South. What they have in common is hostility to the US, which goes back to the old days of the Cold War, when the left in Latin America or in Africa tended to be anti-American and sympathetic to the Soviet side without necessarily being full-scale communist.

Weltwoche: Let’s focus on the main adversary that you have identified: China. In a previous interview, you concluded that “behind China’s patina of capitalism, there is still a communist party in charge that is driven by Marxism and Leninism.” Recalling your time as a visiting professor in Tsinghua, you said two remarkable things. First, that you have witnessed how Xi has explicitly prohibited teachings of democracy, the rule of law, and Western ideas at Chinese university.

Ferguson: Yes, I watched this change when I was visiting at Tsinghua a few years ago. The atmosphere of Tsinghua was quite open, and my Chinese colleagues and students were quite uninhibited about discussing Chinese history and politics. That really changed over time until, at the end people would say, “Please don’t mention the cultural revolution. It’s very sensitive.” Or, “Be careful what you say because you can say it, but it’s difficult for us if you do.” You could see the atmosphere change.

Weltwoche: Your second remark was more disturbing. You said that you’ve “observed that Xi Jinping has told the party to prepare for war.” What kind of a war, in your view, are the Chinese preparing for?

Ferguson: I think the war that is being prepared for is quite obviously multidimensional. If you look at what Xi Jinping says in speeches, at party events, or read what appears in other party publications, he’s preoccupied not only with the possibility of conventional war over Taiwan but with the potential for information war. That means propaganda and cyber warfare, information, disinformation, and misinformation.

There’s a potential for space war because anti-satellite weaponry is in play, and, of course, there is some risk of nuclear war because, otherwise, why are the Chinese building so many nuclear missiles? We are moving rapidly into the territory of the middle period of the first Cold War when the Soviets acquired something close to parity in nuclear weapons and conventional weapons.

China is catching up very rapidly. Its navy is actually bigger than the US Navy, already. Its nuclear arsenal is not as big, but they’re building it very rapidly. The Chinese have some other weapons that the US is behind with.

Weltwoche: For example?

Ferguson: The Chinese have a much bigger capacity to build drones than the US. It’s easier for China to build a drone swarm. China has hypersonic missiles, which the US is somewhat behind with.

The biggest issue, I think, might be in space, where the Chinese and Russians are clearly seeking some weapons that can disable US military satellite communications which are crucial for how the US military operates. This war can take many forms. It could be as limited as a blockade of Taiwan, which they could do tomorrow, if they wanted.

It could be as large scale as a full blown naval war in the South China Sea. Watch what’s going on around the Philippines. It could ultimately be World War III. The Chinese are building the capability to take on the United States in every domain across the spectrum of military power.

Weltwoche: Let’s go back from the Cold War to the hot war on our doorstep: Ukraine. The Russians seem to have the upper hand. It seems almost impossible that Ukrainians, even with the weapons that they get from the West, will get all the territory back that was taken by Putin’s forces. What is at stake in Ukraine? Is the outcome of this war decisive for the future of the West?

Ferguson: I think it’s decisive in the sense that if the US and its allies fail, and Ukraine is defeated, that will signal the biggest reverse that we’ve seen since the Cold War. Although, you couldn’t say Iraq was a triumph, and Afghanistan was certainly a failure, this is a much higher stakes game that’s being played. If Russia wins in Ukraine, then Putin has taken the first step to reconstituting the Russian Empire, and it won’t be the last one he takes because there are other obvious targets for him from Moldova to Lithuania.

We should expect Putin to continue to try to rebuild the Russian Empire (not the Soviet Union, because that’s not really his goal.) It will be very costly to deter him if he’s achieved that first victory.

I think it’s great news that Republicans in Washington finally realized that this can’t be allowed to happen. [Last month, the U.S. House of Representatives has passed a $61-billion-dollar package in military aid for Ukraine.] Speaker of the House Mike Johnson did the right thing. The pro-Russian isolationists lost. Great. This is a good sign.

Weltwoche: Is it not too late for this military aid to make a difference?

Ferguson: I don’t think it’s too late to stabilize the situation. It will take time for Russia to be driven out of Eastern Ukraine, particularly the Donbass region. The most important thing is to prevent Russia consolidating its southern gains, the so-called land bridge territory. Anything along the Black Sea coast is strategically important for Ukraine. That’s really what matters in the short run. Stabilize the line, particularly around Kharkiv, and then make sure that not only is Odessa defended, but that Russia can’t sustain its operations west of Crimea. That’s doable.

The reality is that the Ukrainians were winning at the end of 2022. We then didn’t give them sufficient weaponry to exploit the gains that they made. Then, we expected them, after giving six months of telegraphing, to achieve breakthroughs against the Russian line. By the middle of 2023, it was highly fortified. Western strategists, and I do blame the Biden administration for this, and NATO were generally to blame. They acted as if there was some kind of stable stalemate that was okay. Not many wars end in a tie. It’s not like soccer.

If you’re not winning, at some point, you’re losing. We’ve allowed Ukraine to go from winning to losing by simply giving too little support, and then cutting off the American support altogether at the end of last year. But it’s fixable because the Russians are not as good as all that at infantry operations, because Ukraine was inflicting heavy damage on the Russian Navy, and because Ukraine has introduced a new conscription law. It will be able to rebuild its ground forces.

We’ve left it late, but not too late. It will take years and years and years to get a complete victory. I don’t think the goal should be to get Russia out of everything it has taken since 1991 or since 2014.

Weltwoche: What is the short-term goal?

Ferguson: My definition of victory is that Ukraine is economically and politically viable, that its accession to the European Union and, ideally, NATO can happen, and that Russia’s presence in Eastern Ukraine is never regarded as legitimate, because it’s not. In that way, you can stop the conflict without acceding to Russia’s objectives. I think that’s what our goal should be in the next two or three years.

Weltwoche: You just mentioned the $61 billion package in military aid for Ukraine that was passed in the U.S. Congress. The majority of Republicans voted against the bill. Many of the opponents said that the U.S. should not finance a foreign war while its southern border has fallen. They say that Washington needs to invest that money in the country’s own security. Don’t you think they have a point?

Ferguson: Well, I actually think that this is one of the stupider political arguments of my lifetime. As if the United States is so cash-strapped that it can’t walk and chew gum at the same time.

I think it’s quite true that the situation in the southern border is a scandal. The Biden administration has been extraordinarily negligent in policing that border and in pursuing a rational strategy on asylum and immigration, generally. Just because they’ve screwed that up, it doesn’t mean that Ukraine has to be thrown under a bus.

The United States federal government spends billions of dollars. Actually, its budget is $7 trillion. A tiny fraction of that has gone to supporting Ukraine. Military assistance to Ukraine has been extremely efficient from the point of view of foreign policy goals. No American lives have been lost. The Ukrainians have inflicted colossal damage on the Russian army. They have been highly successful allies. You’re cutting off money to one of your best foreign policy initiatives of the last fifty years? It’s absurd.

The clear answer is you have to do both. It shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. It was stupid politics to tie the two things together. I think a growing number of Republicans, particularly since the attack on Israel on October 7th, realize there is a Cold War. These conflicts are connected. If you let Russia win in Ukraine, that’s a huge win for China and Iran, too.

Why would you do that? Luckily, there are smart Republicans, like Mike Pompeo, who have been making this argument for some time. I think that the Republicans who take Marjorie Taylor Greene’s line or Tucker Carlson’s line are going to look more and more foolish with every passing month, as it becomes clear just how high the stakes are. I think they’re losing this argument, and I think you’ll see, as the year unfolds, that the isolationists themselves become isolated.

Weltwoche: When we talk about the Cold War, we talk about opposing camps, opposing ideologies. What are the core values and shared beliefs that unite the West?

Ferguson: Well, I think the West is partly a historic construct. That’s to say, those countries that, after World War II, banded together to prevent the Soviet Union from creating a global totalitarian empire were doing it mainly, I think, because they saw that empire would ultimately threaten them, but also because we collectively prefer democracy and free institutions to communism or any other form of totalitarianism.

Now, the countries that had been adversaries of the UK and the US in World War II, for example, Germany and Japan, in effect joined the West after 1945 because their attempt at a totalitarian alternative had been a catastrophe. If you look at key supporters of Ukraine, they include countries that were on the, if you like, wrong side in World War II but the right side in the first Cold War.

One way of just thinking about the West is to say, “Look who’s supported Ukraine, who’s actually been giving money or weapons or supporting refugees.” That tells you the list of countries that are today’s West. Of course, when you realize that Japan is one of them, it’s clear that this term “West” doesn't have a whole lot of geographical meaning. You’re really talking about Western Europe, plus Central European countries that have become part of the European Union and NATO, plus North America, plus Australia, which is a very important part of it, plus Japan.

We have, I think, a common commitment to free institutions, even if they vary quite considerably in their institutional structures. There is a common cultural legacy in the English-speaking countries that goes back a very long way, but that’s not crucial because, clearly, there are countries with quite different cultures that are part of the modern West.

Weltwoche: What lessons from the first Cold War might help to win the second? Reagan’s doctrine of ‘peace through strength’ that was based on the Roman maxim “si vis pacem, para bellum” —if you want peace, prepare for war?

Ferguson: I think lesson number one is keep it cold. You don’t want World War III. That’s the whole point of Cold War II, really, to avoid World War III. Lesson number two is if you’re going to fight proxy wars, if you're going to support Ukraine or Israel, or Taiwan, you have to be prepared to go the distance. One of the mistakes the US made was to enter those sorts of conflicts and fail, most obviously in Vietnam. If you think about this from a Ukrainian perspective, Ukraine wants to be South Korea, not South Vietnam. We want to avoid Vietnam.

A third lesson is that you have to talk to the other guys. To talk was a very important way to stabilize the first Cold War by creating negotiations about arms control and a whole lot of other stuff that weren't based on naivety, but were based on an understanding that you had to have conversations, dialog with the other side to reduce the risk of, say, a Cuban missile crisis happening again.

The good thing about Cold War II is we can learn from Cold War I. A really crucial piece of knowledge we acquired in the first Cold War was nuclear deterrence. We understood much better how that works by the end. Unfortunately, we've forgotten all that. You could see we’d forgotten by the way we handled Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. As soon as he started doing that, I said, “You have to tell him that we also have nuclear weapons, and if he uses his, we will use ours.” That's what you do, but we didn't do that.

In fact, we acted really scared and backed away from supplying Ukraine with the fighter planes that they could really have used in that war. We have to remind ourselves that nuclear deterrence means you have to be willing to threaten to use those weapons if the other side threatens to do so. Otherwise, they’re useless. Otherwise, you might as well not have bothered building them. That’s one of the big problems with Joe Biden. He loves to take things off the table that should be on the table.

Weltwoche: There are several threats to the West that you’ve identified in your books and speeches—China, radical Islam—but there is also the challenge from within our Western democracies. We are witnessing a growing polarization, with social media as new battlefields. What dangers arise from the divide in our societies?

Ferguson: One of the mistakes that people commonly make is to use the 20th century to understand the 21st. That’s too narrow a perspective, as I try to argue in a book called The Square and the Tower. The 21st century is very different because of the way information technology has changed the public sphere. You can’t really use mid-20th-century analogies all of the time because information technology was highly centralized and easy to control by powerful governments. We’ve left all that behind.

Now, we inhabit a world of decentralized communication systems which are highly vulnerable because of their openness, and which have potentials for surveillance that really didn’t exist in the Cold War. We actually have more surveillance than George Orwell imagined in “1984.” We also have a kind of unlimited power of expression and network formation so that, obviously, anybody can be a journalist or a publisher if they want to be.

They can use platforms, like Youtube or Whatsapp, to reach extraordinary numbers of people. The bottom line is the world is not the world of Stalin or Hitler. It’s not even the world of Khrushchev and Kennedy.

Weltwoche: Which means that the new cold war is more complex and difficult to fight?

Ferguson: That means that it’s harder for us to maintain our unity as a society because of all the ways in which the algorithms cause polarization. They’re designed to promote extreme ideas because they’re more engaging, and you’re trying to sell ads. You want people to be engaged, so you sell clickbait. That’s how it works.

At the same time, we are highly susceptible to penetration by hostile actors. There are possibilities for manipulation of Western populations that the KGB never had that, today, the FSB has and troll farms that the Russians run. We’re both more divided and more easily penetrated by the enemy, and we defy ourselves. It doesn’t need the Russians to generate all the content. We’re pretty good at generating crazy content for ourselves. This does change the nature of the Cold War. I think it makes it harder for open societies.

Niall Ferguson is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and co-founder of the University of Austin, which will begin teaching this fall.

1 Kommentare zu “The New Cold War”

Schreiben Sie einen Kommentar Antworten abbrechen

Sie müssen sich anmelden, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.

Noch kein Kommentar-Konto? Hier kostenlos registrieren.

Netiquette

Die Kommentare auf weltwoche.ch/weltwoche.de sollen den offenen Meinungsaustausch unter den Lesern ermöglichen. Es ist uns ein wichtiges Anliegen, dass in allen Kommentarspalten fair und sachlich debattiert wird.

Das Nutzen der Kommentarfunktion bedeutet ein Einverständnis mit unseren Richtlinien.

Scharfe, sachbezogene Kritik am Inhalt des Artikels, an Protagonisten des Zeitgeschehens oder an Beiträgen anderer Forumsteilnehmer ist erwünscht, solange sie höflich vorgetragen wird. Wählen Sie im Zweifelsfall den subtileren Ausdruck.

Unzulässig sind:

- Antisemitismus / Rassismus

- Aufrufe zur Gewalt / Billigung von Gewalt

- Begriffe unter der Gürtellinie/Fäkalsprache

- Beleidigung anderer Forumsteilnehmer / verächtliche Abänderungen von deren Namen

- Vergleiche demokratischer Politiker/Institutionen/Personen mit dem Nationalsozialismus

- Justiziable Unterstellungen/Unwahrheiten

- Kommentare oder ganze Abschnitte nur in Grossbuchstaben

- Kommentare, die nichts mit dem Thema des Artikels zu tun haben

- Kommentarserien (zwei oder mehrere Kommentare hintereinander um die Zeichenbeschränkung zu umgehen)

- Kommentare, die kommerzieller Natur sind

- Kommentare mit vielen Sonderzeichen oder solche, die in Rechtschreibung und Interpunktion mangelhaft sind

- Kommentare, die mehr als einen externen Link enthalten

- Kommentare, die einen Link zu dubiosen Seiten enthalten

- Kommentare, die nur einen Link enthalten ohne beschreibenden Kontext dazu

- Kommentare, die nicht auf Deutsch sind. Die Forumssprache ist Deutsch.

Als Medium, das der freien Meinungsäusserung verpflichtet ist, handhabt die Weltwoche Verlags AG die Veröffentlichung von Kommentaren liberal. Die Prüfer sind bemüht, die Beurteilung mit Augenmass und gesundem Menschenverstand vorzunehmen.

Die Online-Redaktion behält sich vor, Kommentare nach eigenem Gutdünken und ohne Angabe von Gründen nicht freizugeben. Wir bitten Sie zu beachten, dass Kommentarprüfung keine exakte Wissenschaft ist und es auch zu Fehlentscheidungen kommen kann. Es besteht jedoch grundsätzlich kein Recht darauf, dass ein Kommentar veröffentlich wird. Über einzelne nicht-veröffentlichte Kommentare kann keine Korrespondenz geführt werden. Weiter behält sich die Redaktion das Recht vor, Kürzungen vorzunehmen.

Urs Gehriger

Urs Gehriger

Why should BRICS states not standing up for free market as much as the so called free western countries proclaiming (partially falsly) by themselves? This one of the biggest LYING narratives. Whenever USA is put into corner, they are imposing protective duties or simply invading countries to make sure they have guaranteed access to fossil energy. FRANCE is still highly making profit from the CFA-zone in Africa without bringing own adequate performance, let’s say a modern form of robber baronism.